100 Shooting Review Report - PhilaDAO Data Dashboard

In September of 2020, Philadelphia City Council passed two resolutions to authorize the Committee on Public Safety and the Special Committee on Gun Violence to hold hearings and request information about gun violence in Philadelphia. An interagency group consisting of the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office, the Philadelphia Police Department, the Department of Public Health, the Defender Association, the First Judicial District, the City Controller’s Office, and the Managing Director’s Office was formed to explore the issue. In January of 2022, a report was released co-authored by several agencies responsive to Council’s request for information. The Executive Summary, Establishment of Committee, and Goals and Policy Considerations sections were co-written by the interagency working group. The Last 100 Shooting Data Analysis, Recommendations, and Appendix sections are excerpts from the larger 100 Shooting Review Committee report that were authored by the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office. The full report, including parts authored by other agencies, is available on the Research portal, or as PDF via direct download.

Table of Contents

- 1. Executive Summary

- 2. Establishment of Committee

- 3. Last 100 Shooting Data Analysis

- 5. Goals and Policy Considerations

- 6. Recommendations

- Appendix 7: DAO Supplemental Materials

- DAO 1. Maps of Structural Racism in Philadelphia

- DAO 2. Data Sharing and Data Limitations

- DAO 3. Arrest Rates in Shooting Cases

- DAO 4. Review of 100 People Most Recently Arrested for Shootings and All Shooting Arrestees Since 2015

- DAO 5. The (un)Predictive Nature of Prior Arrests and Demographics on Future Shootings

- DAO 6. Analysis of Factors Influencing Fatal and Non-Fatal Shooting Clearance Rates

- DAO 7. Arrest Rates and Shootings Per Month

- DAO 8. Time-to-Arrest in Cleared Fatal and Non-Fatal Shootings and Replication of Cook et al. (2019)

- DAO 9. Poster on Gun Cases by Amaral, Loeffler, Ridgeway (2021)

- DAO 10. DAO Analysis of 388 Dismissed or Withdrawn Illegal Gun Possession Cases

- DAO 11. Police Vehicle and Pedestrian Stops

- DAO 12. Conviction Rates and Open Shooting, Non-Fatal Shooting, and Illegal Gun Possession Cases During COVID-19

- DAO 13. Preliminary Hearing and Case Outcomes for Weekly VUFA/NFS Case Review

- DAO 14. Examples of Recent Gun Violence Task Force (GVTF) Investigations

- DAO 15. Gun Possession Arrests and Re-arrests for a Future Shooting

- DAO 16. Data on Gun Sales and “Crime Guns” Seized

- DAO 17. Enforcement of Illegal Gun Possession

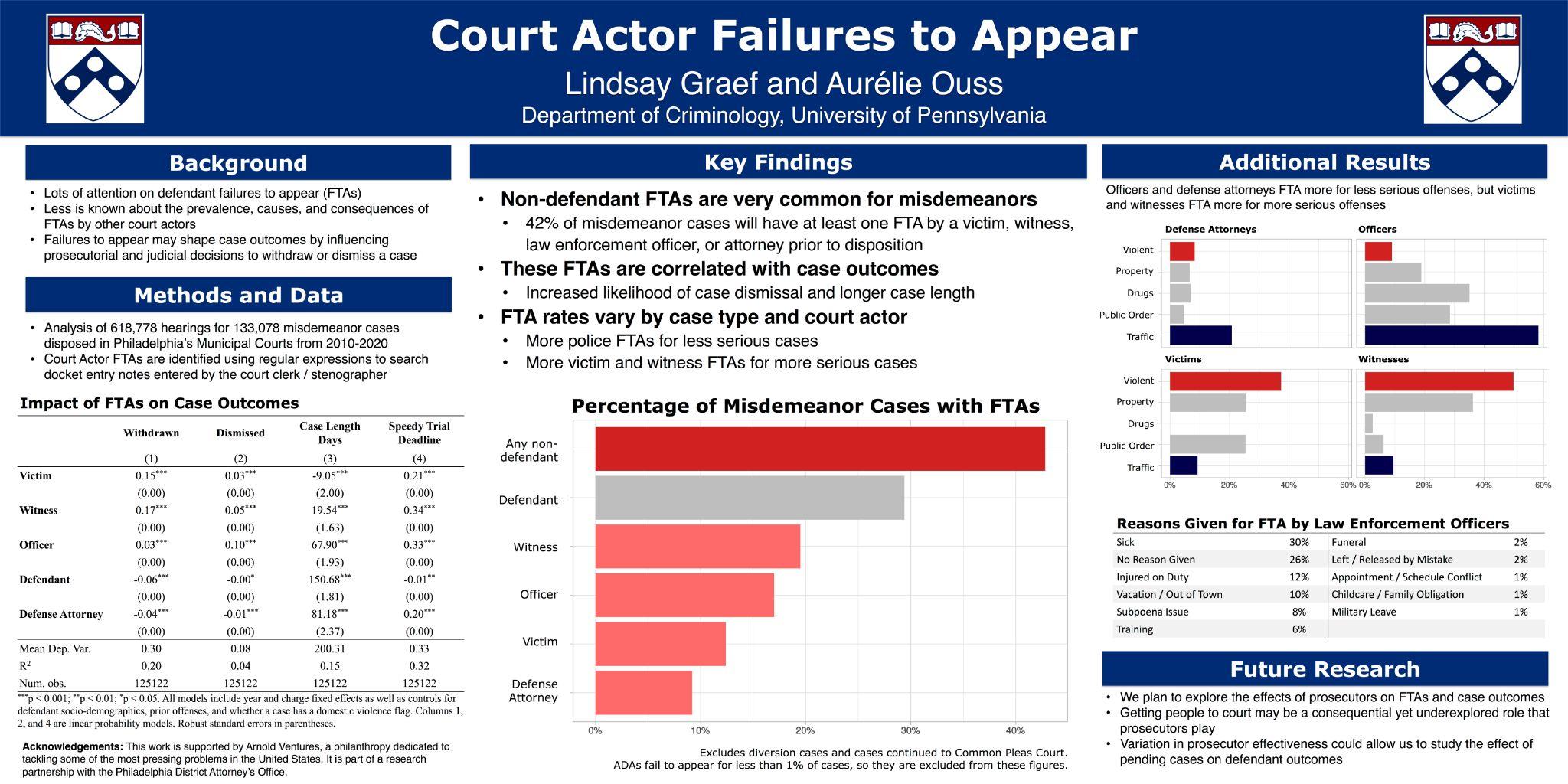

- DAO 18. Poster on Court Actor Failures to Appear by Graef and Ouss (2021)

- Footnotes

- Executive Summary

On September 10, 2020, City Council passed Resolution #200436, authorizing the Committee on Public Safety and the Special Committee on Gun Violence Prevention to hold hearings on the current state of gun violence in Philadelphia and to receive actionable recommendations to address the gun violence crisis. Specifically, the resolution along with subsequent Resolution #210703 and committee discussions sought information on and examination of (1) the circumstances shared by those accused of committing the last 100 shootings, (2) the source of firearms used to commit violent crime in the city, (3) any prior contacts the arrestee had with the criminal justice system, and (4) the trend of gun case disposition, bail and recidivism.

This report reflects joint efforts by numerous city agencies to respond to the resolution, specifically by reviewing available data, studies, and evidence-based practices throughout the United States. The inter-agency collaboration has been collectively referred to as the Philadelphia Interagency Research and Public Safety Collaborative (PIRPSC) and includes the following organizations (those with a * were directly responsible for this report):

- Controller’s Office

- Defender Association of Philadelphia (“Defender Association”) *

- Department of Public Health (“DPH” or “PDPH”) *

- District Attorney’s Office (“DAO”) *

- First Judicial District (“FJD”)

- Managing Director’s Office (“MDO”) *

- PA Attorney General

- Police Department (“PPD”) *

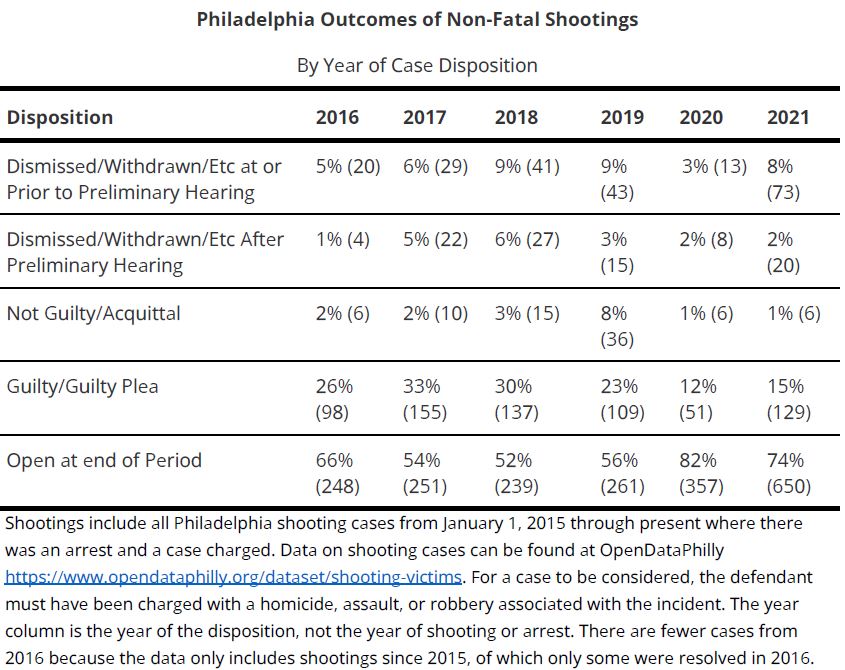

Firearm violence in Philadelphia is a public health crisis. In 2021, Philadelphia suffered a record number of fatal criminal shooting victims (501) and non-fatal criminal shooting victims (1,850)1. Philadelphia has also experienced extraordinary recent increases in arrests for illegal firearm possession and crime guns recovered, while the Commonwealth has recorded record gun sales in 2020. Despite this crisis in gun violence, shooting arrest rates remain low, conviction rates in illegal gun possession cases have been declining since 2015, and conviction rates in shooting cases declined between 2015 and 2019 and increased modestly in 2020 and 2021.

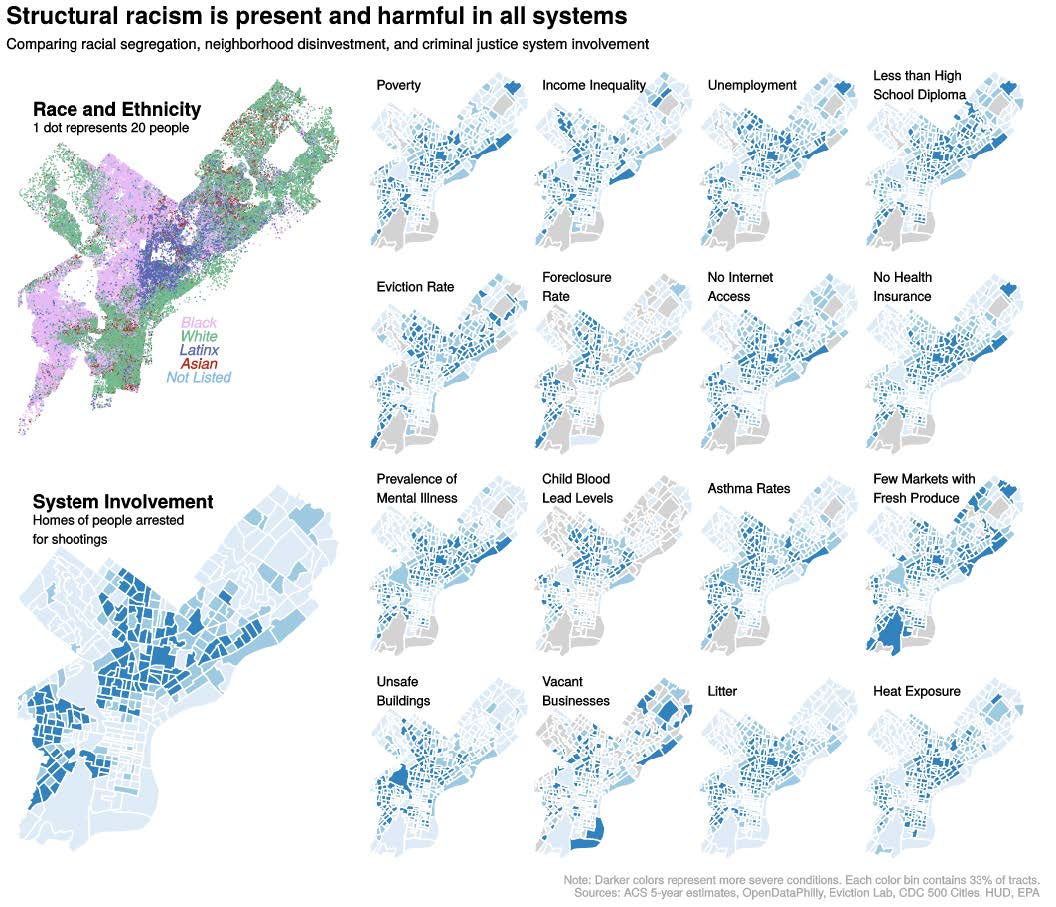

Firearm violence in Philadelphia is a racial justice crisis. Shootings disproportionately impact Black communities: in Philadelphia over 80% of shooting victims and 79% of arrestees have been Black since 2015. Both victims and arrestees overwhelmingly come from disadvantaged neighborhoods that are majority non-white, have high rates of poverty and unemployment, and less likely to have a high school degree or diploma. Endemic violence in these communities means that the vast majority of those arrested for gun violence have themselves been previously traumatized, often as a witness to previous violent acts; over 80% have previously accessed or been screened for behavioral health services through the City.

Because the causes of gun violence are complex and varied, so are the solutions. Addressing the gun violence crisis requires a comprehensive strategy with elements of enforcement, intervention, and prevention to achieve both short-term and long-term reductions in gun crimes. Collaboration among city agencies, including law enforcement and non-law enforcement agencies is critical to successfully implement such a comprehensive strategy.

Reviews of evidence-based practices, along with data analysis of local data, have helped us to come to key findings related to gun violence in Philadelphia and have informed recommendations to stem that violence. Readers are encouraged to read both the summary, below, as well as the report in its entirety to understand the context of our recommendations as well as the limitations in both our data and data analyses.

Key Findings

General Findings on Shootings

- Victims and arrestees for shootings tend to be male, people of color, 18-35 years old, and have a prior criminal history. Most arrestees have used non-criminal city services, with the most common being behavioral health services, and have previously witnessed violence.

- Arrestee contacts with city agencies (both criminal and non-criminal) often occur several years prior to being arrested in a shooting incident, with many contacts happening before the age of 18.

- Arguments were the most commonly identified shooting motive (50% of shootings). Drug trafficking/transactions was the second most common motivation (18%).

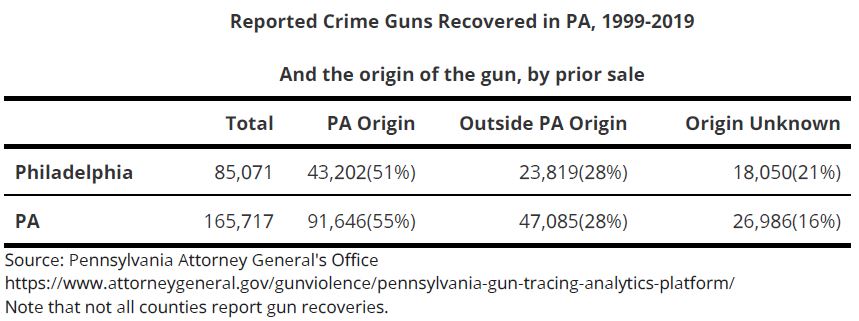

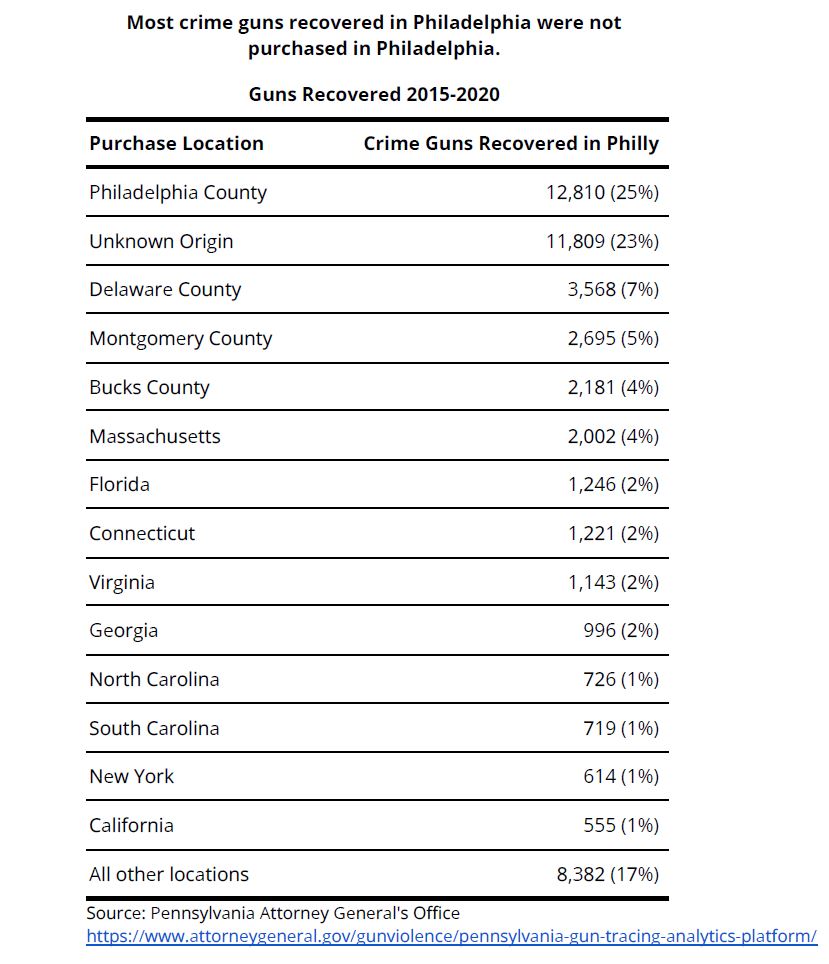

- When crime-guns are recovered, they tend to be semi-automatic pistols that were first purchased in Pennsylvania more than 3 years ago. Because guns may change ownership both legally and illegally, it is not possible to know where the most recent sale was made. Approximately 1 in 4 crime guns were originally purchased outside of Pennsylvania.

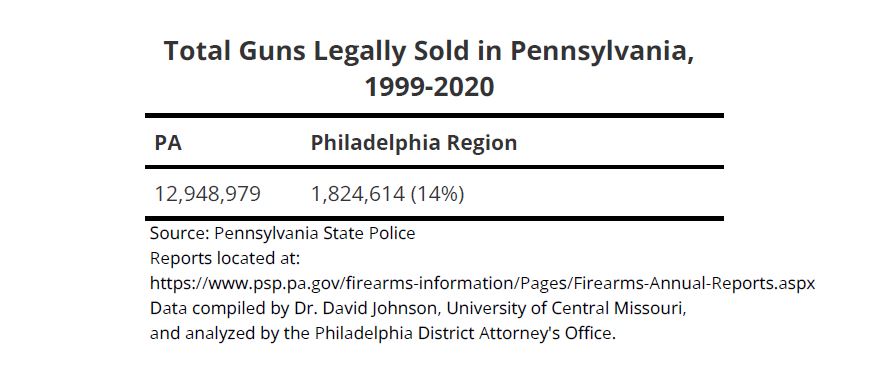

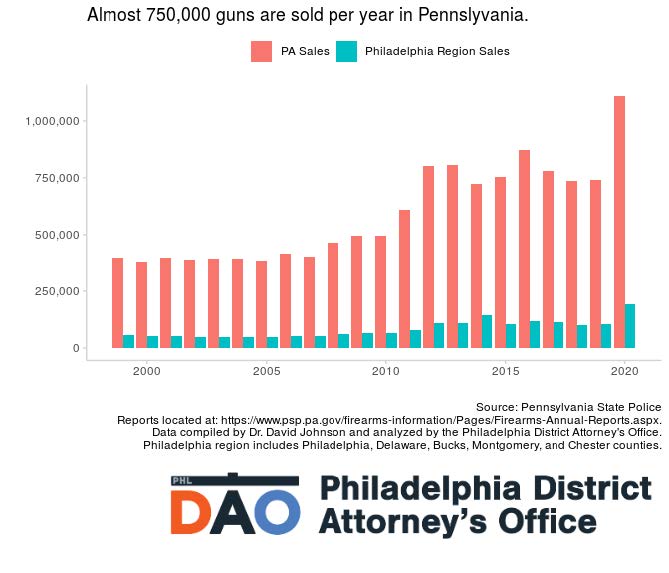

- Gun sales have skyrocketed in Pennsylvania in recent years. In 2000, fewer than 400,000 guns were sold in Pennsylvania; in 2020, over 1 million were sold.

Arrest

- Clearance rates in shooting cases are low. For example, only 37% of fatal shootings and 18% of non-fatal shootings in 2020 have been cleared2. Out of 9,042 shooting victims between 2015 and 2020 in Philadelphia, 6,910 have not been cleared.

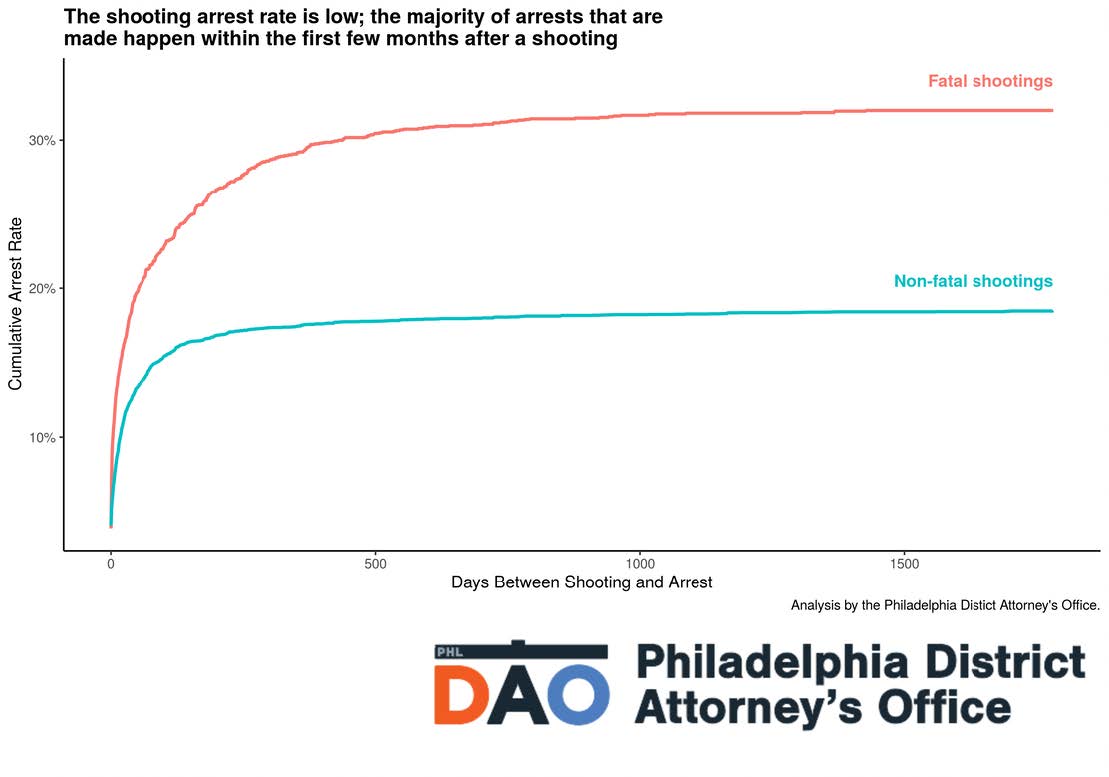

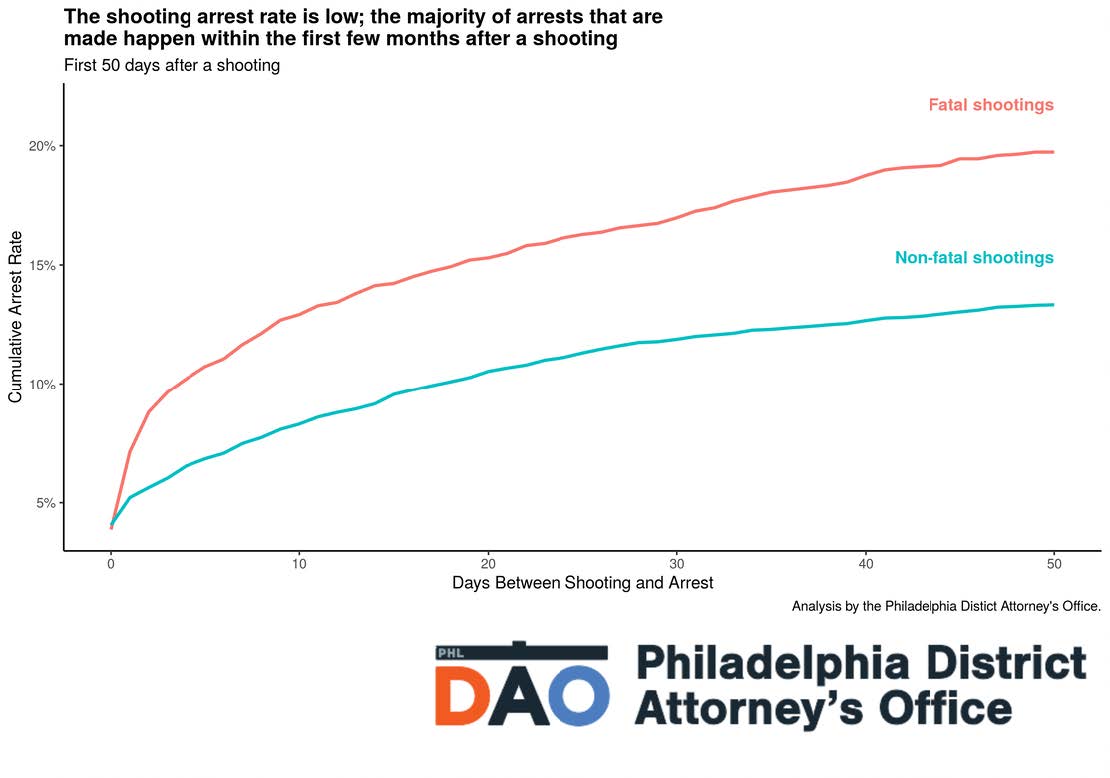

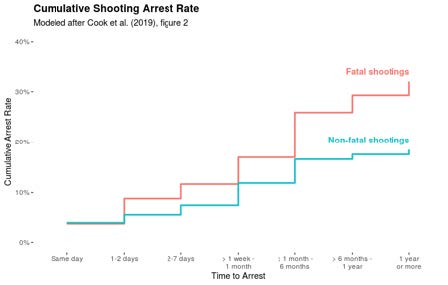

- Arrests for non-fatal and fatal shootings tend to happen within the first few months. 75% of non-fatal shooting arrests occur within 61 days; 75% of fatal shooting arrests occur within 125 days of the shooting.

- Non-fatal shootings are more likely to be solved in months with fewer shootings, when the investigation is done by a PPD unit with more detectives, and where PPD’s Special Investigations Unit (SIU) investigated the incident.

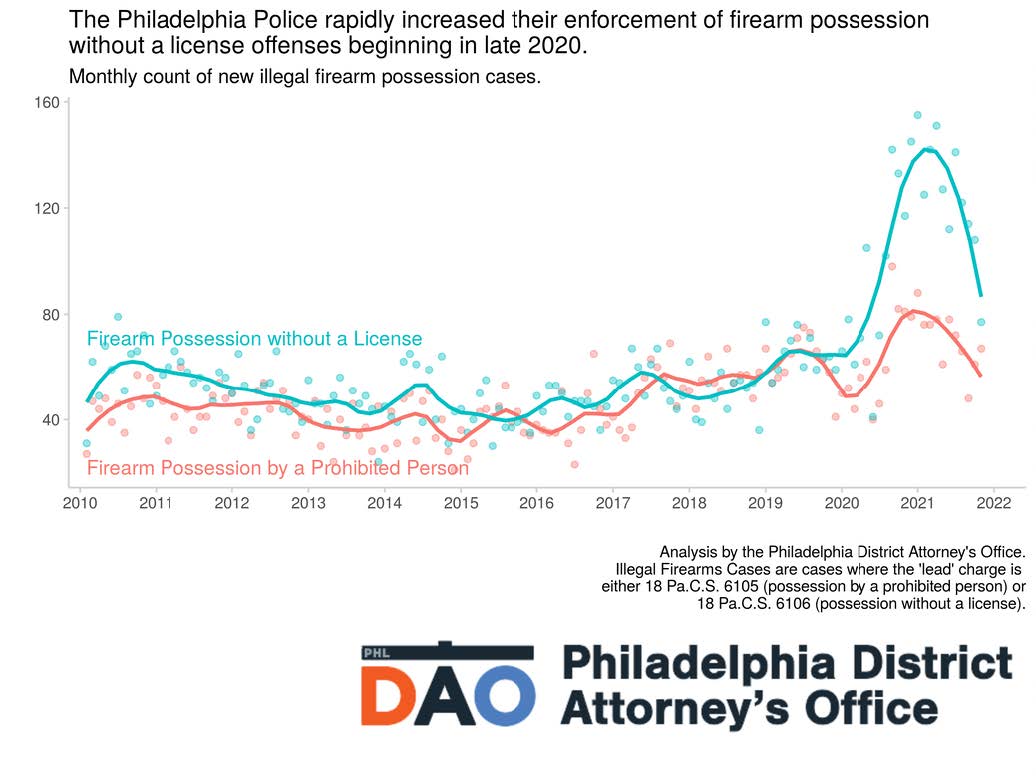

- There has been a marked increase in the number of people arrested in Philadelphia for illegal gun possession (without the accusation of any additional offense)3. That increase is largely due to a doubling in arrests for illegal possession of a firearm without a license since 2018. Arrests for possession of a firearm by a prohibited person have also increased during that time period, but more modestly.

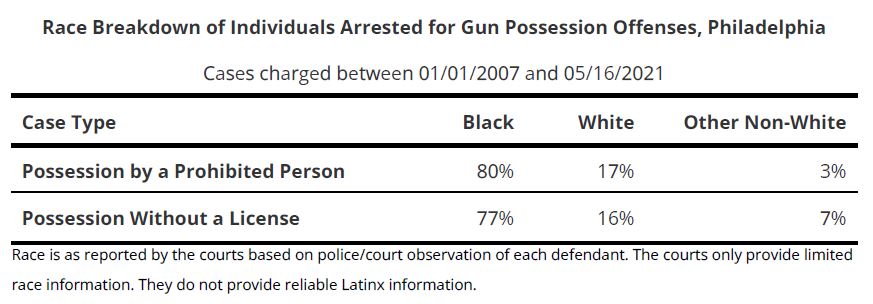

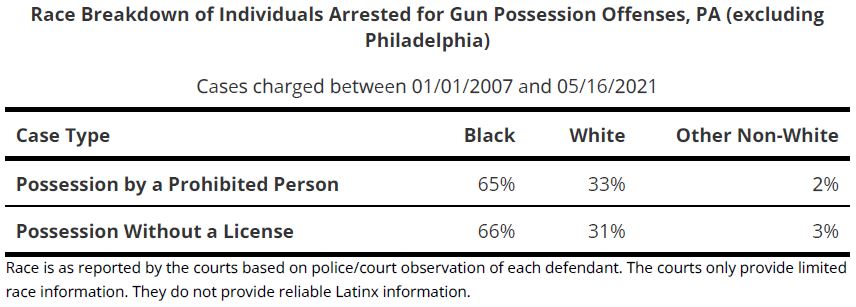

- There is a large disparate impact in illegal gun possession arrests: approximately 4 in 5 people arrested for both primary types of illegal gun possession are Black. Additionally, much of the increase in illegal gun possession arrests have been of young people carrying firearms without a license.

Case Processing

- Both the initial and final bail amount set by courts in illegal possession of firearms cases declined between 2015 and 2019, but increased in 2020 and 2021. As bail decreased along with the increase in the use of unsecured bail, the proportion of cases where bail was posted increased for both types of illegal firearm possession. In 2021, the median initial bail for illegal gun possession by a prohibited person was $150,000 and was $50,000 for illegal possession without a license4.

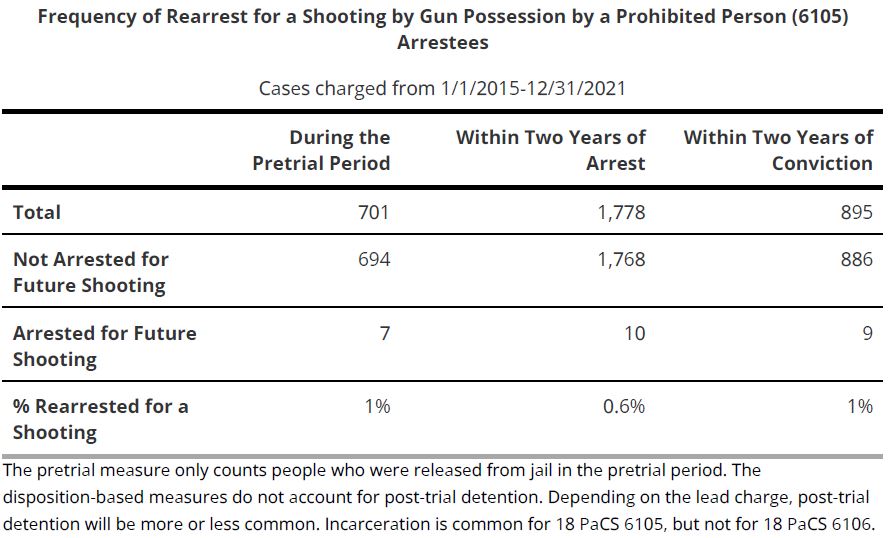

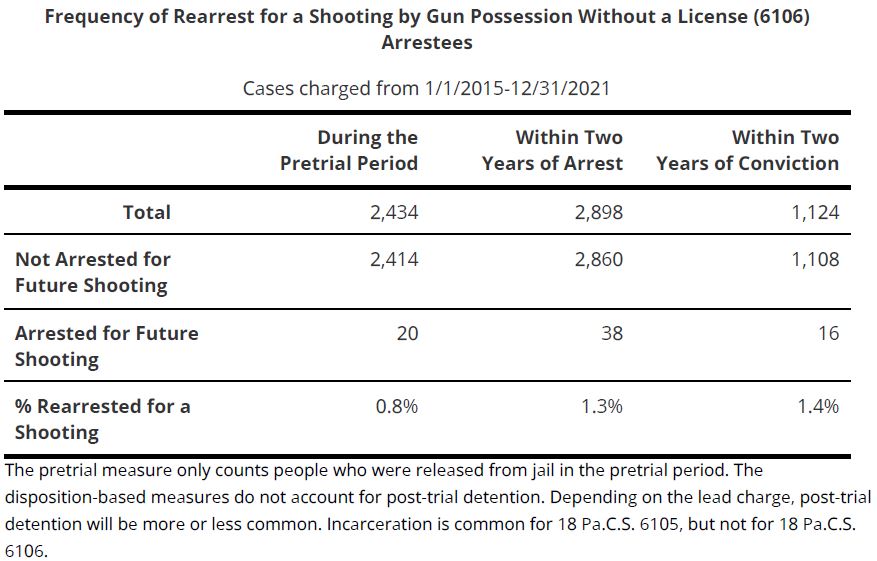

- The rearrest rate for a new gun crime after being released from jail during the pendency of their original illegal possession of firearm case is relatively small, but rearrests may nonetheless be concerning. At the time of September 2021 when the analysis was conducted, the rearrest rate increased slightly from 8% in 2015 to 11% in 2019, but returned to 8% in 2020. The rearrest rate for a new violent gun crime remained steady at around 2-4% during the study period, while the rearrest rate for a new illegal gun possession offense rose from 3-4% in 2015-2018 to 6% in 2019-2020. 1% or fewer of the re-arrests were for shootings during the pendency of their original case.

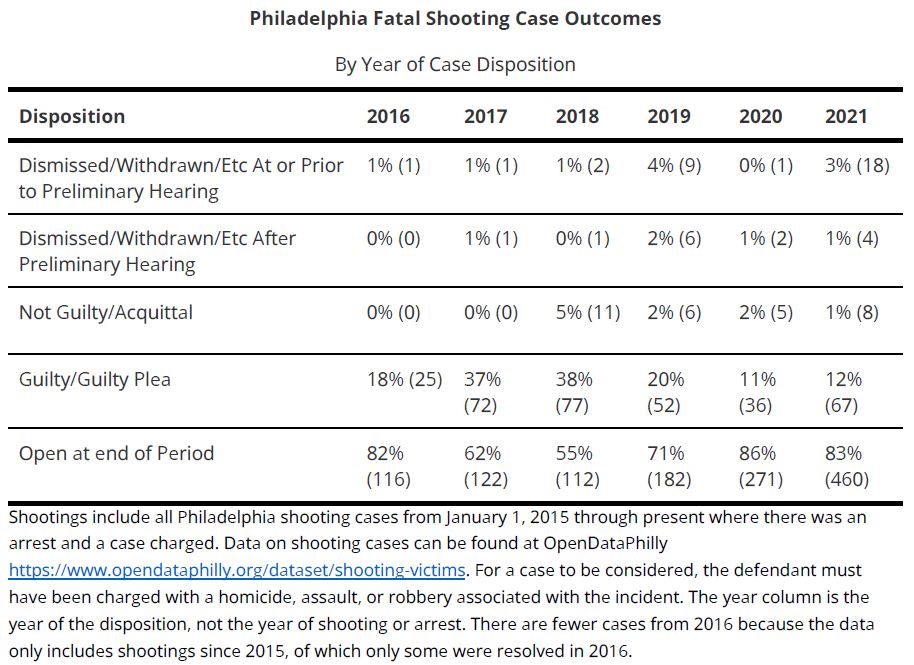

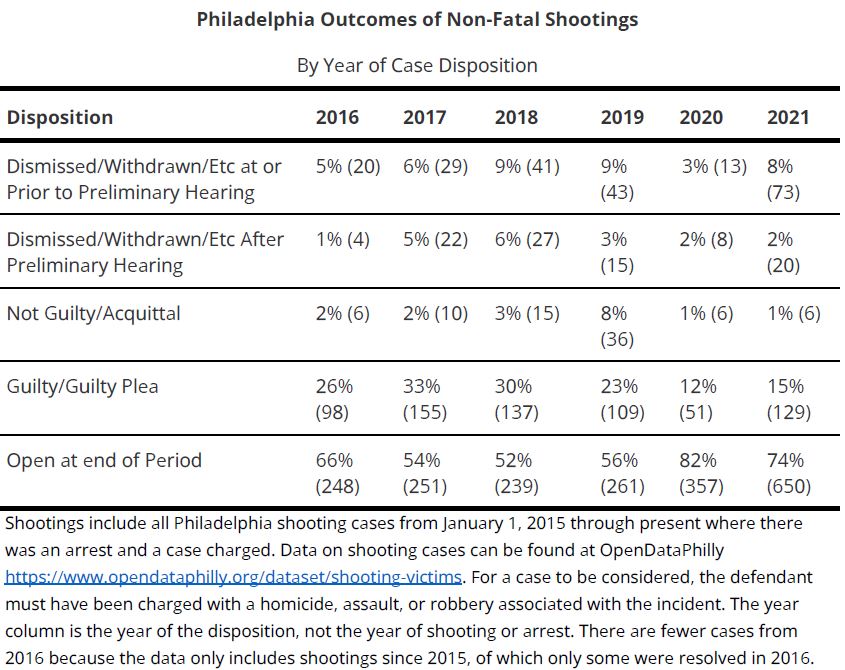

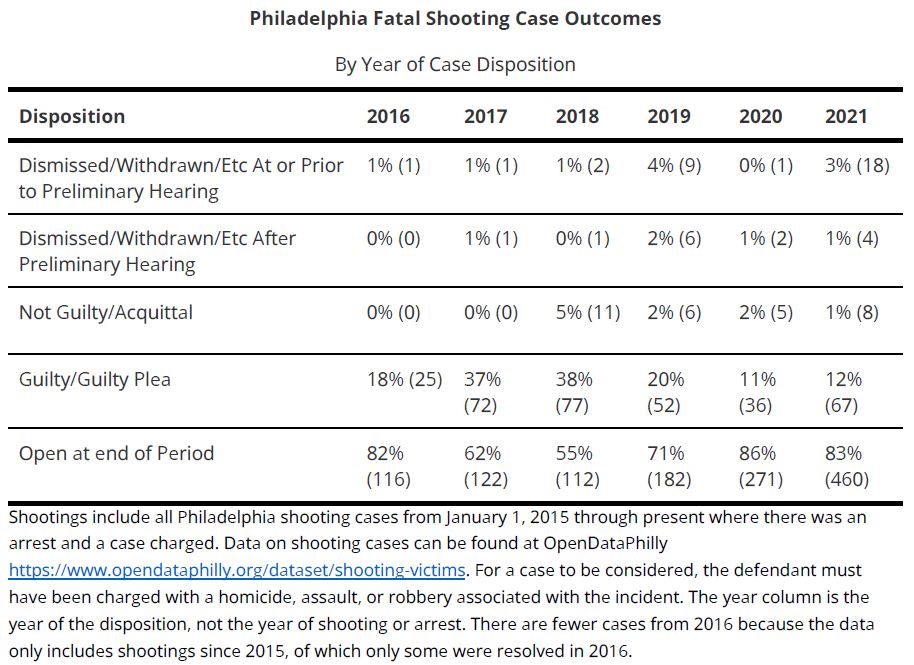

- Conviction rates in shooting cases have fallen steadily since 2015, although had begun to rebound just before the pandemic. Between 2016 and 2020, the fatal shooting conviction rate dropped from 96% to 80%. It dropped less sharply, from 69% to 64%, in non-fatal shootings.

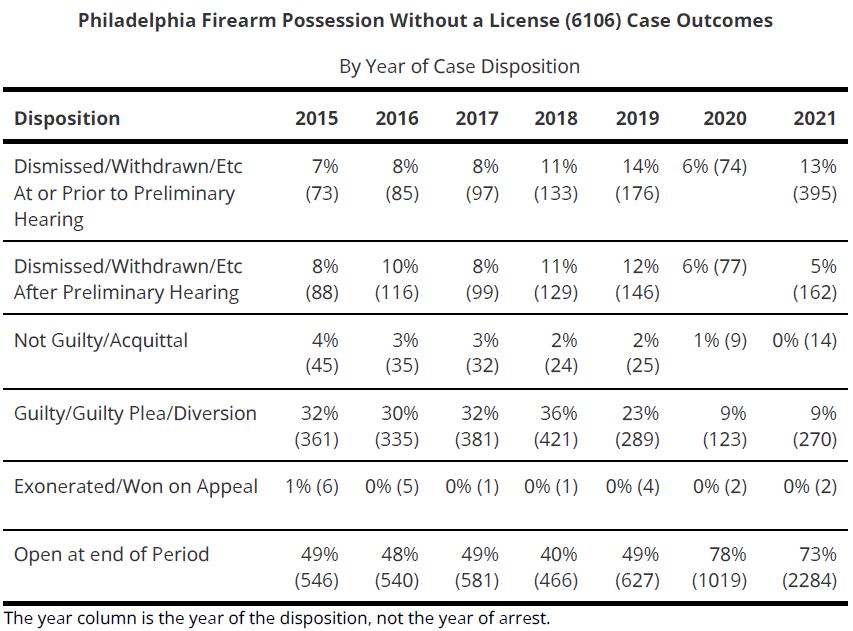

- Conviction rates in both types of illegal gun possession cases have fallen steadily since 2015 (from about 65% in 2015 to about 45% in 2020); notably, this declining trend is a long-term trend predating the pandemic, and the court closure alone will not explain this.

- The courts have had very limited capacity to try cases during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially cases needing civilian witnesses and juries. This has resulted in a large backlog of open cases in 2020 and 2021. For example, at the end of 2019 there were 1,685 pending cases involving fatal or non-fatal shootings or possession of a firearm by a prohibited person or without a license. In mid-December 2021, there were 4,571 open cases for those offenses, an increase of 171%.

- A review of nearly 400 dismissed and withdrawn illegal gun possession cases conducted by the DAO showed an increase in “constructive possession” cases among dismissed and withdrawn illegal gun possession cases in recent years. Constructive possession cases arise when no one physically possesses a gun illegally (e.g. the gun may be under a seat in a car full of people), making the cases harder to prove.

- Approximately half of illegal gun possession cases were dismissed because of the failure of the victim, witness, or police officer to appear for court proceedings. Improving victim, witness, and police officer court appearances is within the control of system actors.

- The DAO and PPD instituted a project to collaboratively review each new non-fatal shooting and gun possession by a prohibited person case in December 2020. Of the cases involved in that collaboration that received a preliminary hearing in its first year, 81% successfully passed the preliminary hearing stage, a significant improvement over rates prior to the collaboration5.

Recommendations

Based on the key findings, additional data analyses, and reviews of evidence-based practices, the agencies make the following recommendations. We note at the outset that all of these recommendations are not unanimous. Even among those with broader support, they will require continued collaboration between system and community stakeholders to ensure implementation in a manner that promotes public safety and fairness. Agencies outline their specific positions on how best to implement these recommendations in the full report. We encourage readers to review each agencies’ sections as there is diversity of opinion between stakeholders as to implementation strategies. Note that endorsement and support are different from prioritization. Many of the recommendations will require funding, and discussions on prioritization under budgetary constraints also need to be held.

Enforcement6

- Incorporate the voices of people with lived experience in developing effective enforcement strategies tailored to their neighborhoods.

- Improve arrest rates in shooting cases by creating a centralized non-fatal shooting investigation team within the PPD and further investing in better forensic technology (e.g., expanding the staffing and space available to PPD’s office of forensic services, investments in technology to test ballistic evidence for DNA, and investment in equipment to conduct forensic cell phone analysis).

- Continue the weekly collaborative review of non-fatal and illegal firearm possession cases by the PPD and DAO; consider expanding it and including other local, state, and federal justice system actors to monitor the trend of gun violence and case dispositions throughout the lifecycle of the cases. Continuous monitoring along with collaborative reviews help address investigative shortcomings and improve the overall law enforcement practices

- Establish dedicated courtrooms for illegal gun possession cases at the Common Pleas Courts so as to streamline the overall process, minimize the risk of re-arrests, improve case processing time, increase education on gun safety, and strengthen individualized case assessment. Having dedicated resources among stakeholders (courts, defenses, and prosecution) will help thoroughly assess individual cases and their risk to determine the best treatment that may range from diversion to incarceration, while simultaneously reducing the time from arrest to disposition. Notably, dedicated courtrooms for illegal gun possession cases already exist at the Municipal Court level.

- Reduce failures of victims and witnesses to appear in criminal cases by providing more support to victims and witnesses (transportation, better follow up), investing in technology to allow for both court-reminder texting to victims and witnesses and provision of transportation vouchers, establishing stronger accountability for police officer failures to appear, and striving to build trust in the overall criminal justice system.

- Invest in victim and witness relocation, by providing more funds for relocation, expanding eligibility for relocation, and improving relocation outcomes by allowing people to be moved further from their homes and into neighborhoods with less violence.

- Advocate for legislation to increase the amount of information that needs to be collected from gun purchasers, to further deter “straw purchasing.”. And request state and federal law enforcement partners increase inspections of federally licensed gun dealers who have been found to be the original source of guns ultimately used in crimes.

- Implement Data-Driven Approaches to Crime and Traffic Safety (DDACTS) that can reduce not only violent crimes but also traffic crashes, when/where these two types of hotspots overlap, through data analysis, high visibility patrols, and publicity strategies. Operational guides of DDACTS emphasize its preventive focus and community partnerships, and DDACTS can support the city’s Vision Zero project.

Intervention

- Include community voices in continued collaboration between city and community stakeholders to develop and implement strategies that build trust and public confidence in local government.

- Prioritize 311 responses and other city services in crime hot spots. Research suggests that addressing environmental factors (e.g., cleaning up trash, fixing and improving street lighting) will result in a significant reduction in violent crimes. City departments’ efforts can be tied to performance-based budgeting for environmental improvements.

- Invest in interventions focused on those of highest vulnerability, such as Cure Violence, the READI model, or Advance Peace. Although each program is different, they all hold the potential to lift those most vulnerable from the cycle of violence and connect them to necessary trauma healing, employment, and support. Collectively, they actively engage at-risk communities and individuals through credible messengers, provision of support services such as cognitive behavioral therapy and job training/placement, paid mentoring, and healing of trauma.

- Develop more victim-centered systems and invest in robust, community-based, culturally competent victim services.

- Advocate on the state level to expand availability of state and federal funding for Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs (HVIP), which have been proven to significantly lower the risk of violent reinjury or future violence perpetration after hospital discharge.

- Invest in technologies that can help to coordinate services for victims and witnesses through community-based organizations, help victims to fill out paperwork to receive victim compensation money.

Prevention

- Incorporate the voices of those with lived experience in any prevention efforts.

- Increase positive interactions between community members and police officers; this may range from positive interactions during officers’ day-to-day patrols (e.g., mere encounters and business checks) to formalized home visits as well as community outreach/meetings.

- Dedicate investment of resources in neighborhoods where chronic disinvestment has crippled community supports, health, and public safety, such as in historically “red-lined” communities and those facing the most violence. These investments should be focused on improving neighborhoods and can include such evidence-based strategies as greening vacant lots, improving street lighting, planting trees, better street cleaning and trash pickup, repairing occupied homes, and remediating abandoned houses. It should also include prioritization of 311 responses to these neighborhoods.

- Expand foot patrols with emphasis on community engagement and positive interactions, correct the current officer shortage through increased hiring, and invest in cell phones for police officers. Research in Philadelphia found that the foot patrols resulted in a significant reduction in violent crimes, when implemented properly with the right amount of resources.

- Prioritize justice system involved people residing in communities with high levels of violence for directed city support services such as eviction protection, homeownership supports (repairs, improvements, purchasing), housing, substance abuse or mental health treatment, and workforce development.

- Create a fund modeled on the Chicago Fund for Safe and Peaceful Communities, to increase private and institutional funding supporting Philadelphia-based community organizations that work to prevent and intervene in gun violence.

- Commit resources to transparently evaluate all violence prevention and intervention efforts and outline plans to expand and scale those that work and end those that do not.

- Increase trust between law enforcement and community members by increasing non-enforcement interactions with police (perhaps through increased community-based policing and foot patrols), reducing law enforcement responses to minor events that currently lead to misdemeanor arrests/charges, and reducing traffic stops for minor code enforcement (e.g., broken tail lights).

- Invest in and expand the DAO’s collaborative intelligence, investigative, community-centered, and victim-centered efforts, all of which are aimed at effective prosecution of gun violence, intervention in communities that suffer from gun violence, and prevention in underserved and traumatized communities.

- Continue commitment to interagency collaboration bridging law enforcement, public health, and other key stakeholders to identify innovative opportunities for intervention and prevention.

- Direct all relevant city and court-related agencies to collaborate with PIRPSC both by participating in meetings and sharing data. The ability to identify at-risk individuals and neighborhoods to provide supportive services in order to prevent future violence is greatly enhanced with additional relevant data.

- Support PIRPSC in expanding its review of gun violence information to include a large-scale longitudinal study, with expanded data sources including qualitative interviews, comparing victims and perpetrators of gun violence and their interaction with city services to other similarly situated residents of Philadelphia.

- Prioritize evidence-based strategies and tactics that reduce gun-violence. Pilot and rigorously evaluate innovative programs, expanding those that work and ending those that do not.

- Establishment of Committee

In September 2020, Councilmember Jones, joined by Council President Clarke, and Councilmembers Johnson and Gauthier, sponsored Resolution #200436 to address increased gun violence, homicide, and access to firearms in the city of Philadelphia. The resolution, along with subsequent Resolution #210703 authorized the Committee on Public Safety and the Special Committee on Gun Violence to hold hearings to (1) review and examine the circumstances shared by those accused of committing the last 100 shootings, (2) explore the source of firearms used to commit violent crime in the city, (3) evaluate any prior contacts the arrestee had with the criminal justice system, and (4) the trend of gun case disposition, bail and recidivism. The resolutions also recognized the need for criminal justice system stakeholders and community stakeholders to collaborate closely to stem the increases in gun violence.

In response to Council’s call for increased collaboration, a group composed of the Mayor’s Managing Director’s, Controller’s and District Attorney’s Offices, the Department of Public Health, Philadelphia Police Department, First Judicial District, and the Defender Association of Philadelphia was created. We now work together as the Philadelphia Interagency Research and Public Safety Collaborative (PIRPSC), helping our agencies share data, emergent research, and associated ideas. PIRPSC would like to thank the Controller’s Office and First Judicial District for their analysis and discussion during the preparation of this report.

The working group met consistently since September 2020 to explore and report its findings related to the research questions initially posed by City Council. Following initial reports, team members expanded the research agenda to investigate gun case outcomes, shooting incident clearance rates, and witness appearance rates. While focusing on criminal case process improvement, the working group also analyzed arrestees’ prior contacts with city services to identify missed intervention opportunities, researched national best practices and potential partnerships with academics, and worked closely with those with lived experience to recommend short and long term strategies to reduce gun violence in the city.

The group prepared and presented materials to City Council at several special hearings and worked collaboratively to summarize the findings and recommendations from the last two years in December 2021.

- Last 100 Shooting Data Analysis

Analysis Result by DAO

The urgency of Philadelphia’s crisis of fatal and non-fatal shootings will not be met by looking away from shootings. As noted above, City Council has led a valuable “100 Shooter Review,” a title that makes clear what we already know: that shootings are the primary issue. Our efforts must be focused on preventing shootings and holding people who commit shootings accountable, and we should not accept arrests for gun possession as a substitute.14

Above all else, real solutions require that prevention be addressed. The pandemic itself proves, both locally and nationally, that when society shuts down and the moderate prevention that currently exists is stripped away from young people–e.g., no organized sports, closed classrooms, closed houses of faith and associated youth programming, closed recreation centers and swimming pools, closed summer camps and job programs, all leading to increased isolation and disrespectful use of social media–gun violence can increase. The pandemic also proves that when law enforcement and courts are significantly curtailed, intelligent enforcement may suffer and gun violence can increase. Intelligent, modern enforcement primarily directed at fatal and non-fatal shootings and secondarily directed at illegal gun possession by people who appear to be driving gun violence is also essential.

Technology can lighten the burden of investigating and prosecuting fatal and non-fatal shootings. All of government must work together to meaningfully invest in the preventative pro-social resources that atrophied during the pandemic, and in forensic science (both DNA and cell phone forensics) capable of solving massive numbers of new and old cases that remain unsolved. Other improvements in investigation and collaboration among governmental actors are also essential, as the recommendations below indicate.

Gun possession arrests that involve no violent acts present a secondary and important frontier in curbing gun violence, but must be targeted to distinguish between drivers of gun violence who possess firearms illegally and otherwise law-abiding people who are not involved in gun violence. On the one hand, the cases of people charged with 6105 (prohibited person in possession of a firearm) are carefully scrutinized to do individual justice, which will usually look like vigorous prosecution. On the other hand, another criminal charge that applies to people who have no felony conviction (carrying a gun in Philadelphia without having obtained a permit in Philadelphia) is only a felony in Philadelphia. The exact same offense in every other county in Pennsylvania (carrying a firearm without a permit to carry) is only a misdemeanor offense. In an equitable system, a permit to carry would be required everywhere in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania or would be required nowhere. But the legislature’s decision to more punitively criminalize and subject to more collateral consequences only the residents of its most diverse city is inequitable and obviously racist. That kind of selective prosecution against Pennsylvania’s most diverse city has its purpose—the money and power upstate legislatures’ jurisdictions obtain from incarcerating Philadelphians in their prisons (Remster and Kramer, 2019).15 Justice and common sense gun regulation do not look like a commerce in the bodies of Philadelphians held in upstate prisons for doing what is not even a crime in the jurisdictions where they are held.

The role of the District Attorney’s Office is to vigorously, justly, and accurately prosecute people who commit serious and violent crimes. Gun violence has been the most urgent public safety crisis in Philadelphia for decades; as such, the DAO considers the most serious, violent offenses such as homicides, rape, and gun violence our top prosecutorial priority. However, local law enforcement faces numerous challenges in our efforts to reduce shootings: namely, a lack of success in identifying shooters and removing them from communities and decades-long lack of sufficient PPD crime scene personnel and the capacity for widespread use of forensic science to solve crimes.

As part of our role in the 100 Shooting Review Committee, we identify a need to more intensely focus law enforcement efforts on accurately identifying and removing shooters from the streets, and conclude that the current intense focus on illegal gun possession without a license is having no effect on the gun violence crisis and distracts from successfully investigating shootings.16 To reduce and solve shootings we must invest heavily in areas that have historically been neglected in Philadelphia, including through preventative pro-social programming; for shootings that are not prevented, we must invest in forensic science so we have more evidence that can be used to solve shootings and to build overwhelming cases that will result in successful prosecutions; more effective alternatives to criminogenic jails for people who come into contact with the system; and scaling up resources and amenities in communities that have experienced disinvestment for so long, and in community-based organizations working in the places and with the people most impacted by gun violence and our systemic failure to address it adequately or holistically.

The DAO conducted a range of analyses and research to answer the central question posed by City Council’s Special Committee on Gun Violence Prevention: “How can we use the data available to the city to reduce shootings?” Below we present findings relevant to improving shooting incident clearance rates and improving the strength of cases when a shooting results in arrest; improving gun case outcomes; deterrence of illegal firearm possession; and improving witness appearance rates. These results are used to inform the Goals and Policy Considerations and Recommendations in subsequent sections. In addition, the DAO makes recommendations regarding short-term investments in community-driven solutions for prevention, and upstream, long-term investments in communities most impacted by gun violence for sustainable reduction. Please see Appendix 7: DAO 2 for an overview of Data Sharing and Limitations, and we encourage reviewing the supplemental material referenced throughout the DAO analysis.

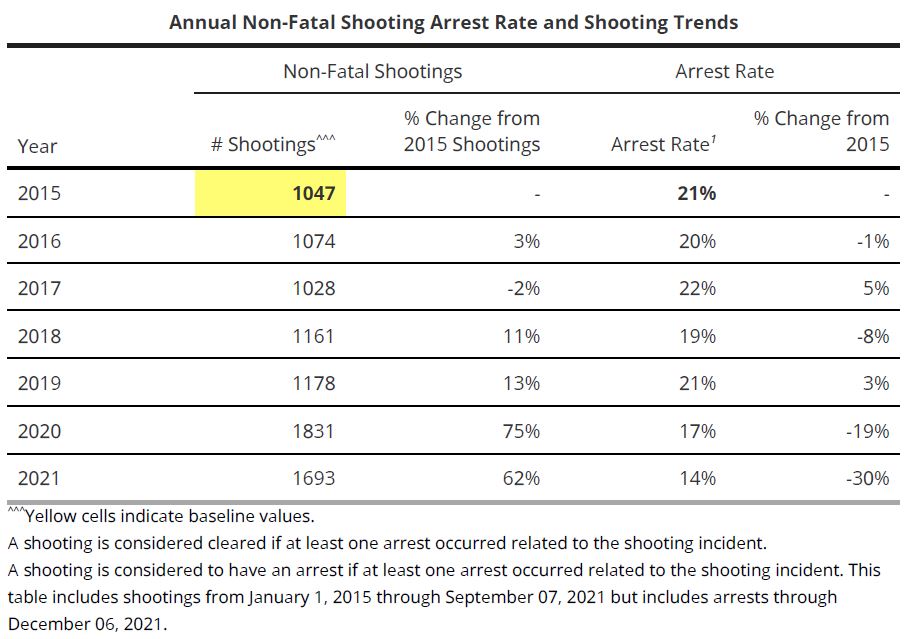

Improving shooting clearance rates

When there is a shooting, we must find those responsible and hold them accountable. If we are unable to do this, we will be unable to stem the tide of gun violence. Unfortunately, the arrest rate in shootings has been very low in recent years in Philadelphia, with a marked drop as the number of shootings has increased. This focus on arrest clearance rates in homicide and non-fatal shootings is both local17 and national.18 Briefly, clearance rates are defined by the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) as the number of resolved cases in a year divided by the number of incidents in the same year (or month, quarter, etc). In this analysis the DAO uses arrest rates: the proportion of incidents where an arrest has been made, regardless of when the arrest was made (See DATA Story on “Clearing up clearance rates” for more details).19

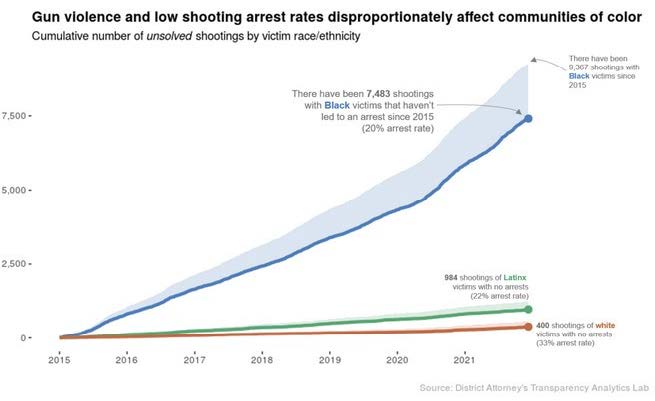

In recent years, four out of five non-fatal shootings in Philadelphia went unsolved (see Appendix 7: DAO 3). Out of 11,306 shootings in Philadelphia since 2015, 8,918 did not result in arrest, including 7,483 shootings in which the victim or survivor was Black (see graphic below). Police make arrests more frequently in fatal shootings, but improvement in fatal shooting investigations is needed as well: two thirds of fatal shootings in Philadelphia are not followed by an arrest (see Appendix 7: DAO 3). It is imperative that we improve the clearance rate in both fatal and non-fatal shootings; this should be our first priority as a city. As 2021 draws to a close, there have been arrests made in only 17% of non-fatal shootings and 28% of fatal shootings that occurred this year.

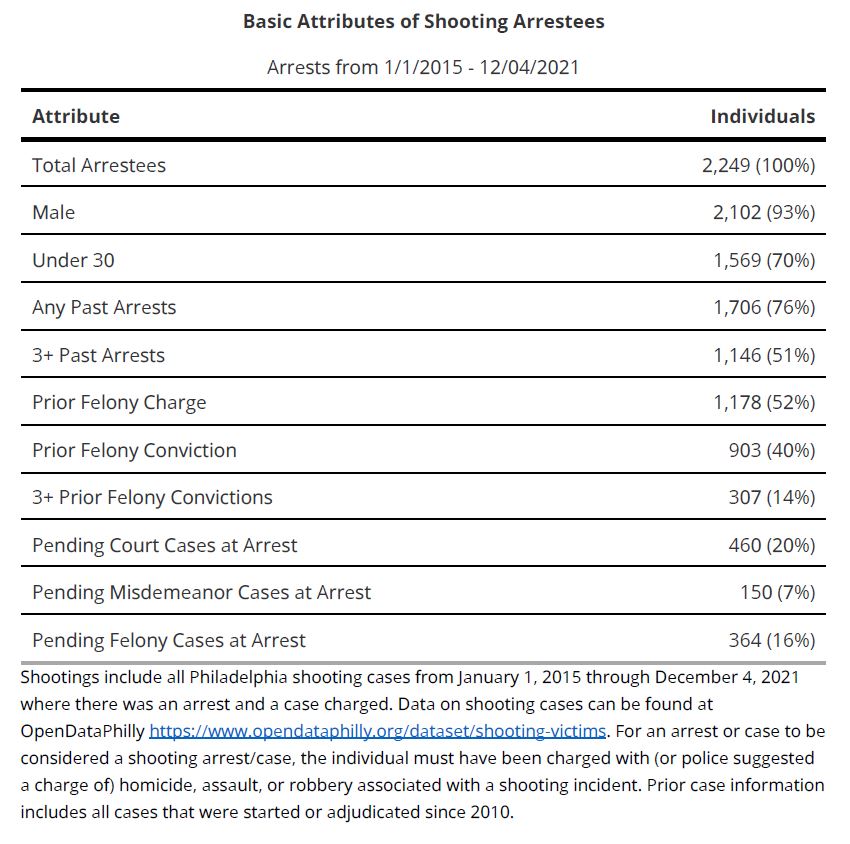

Chart showing that gun violence and low shooting arrest rates disproportionately affect communities of color

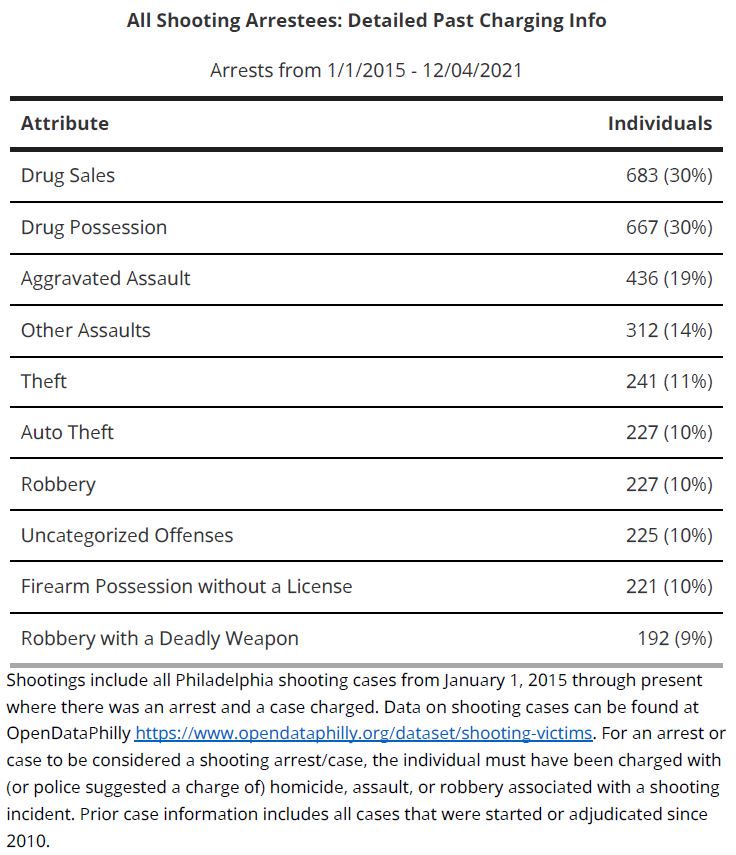

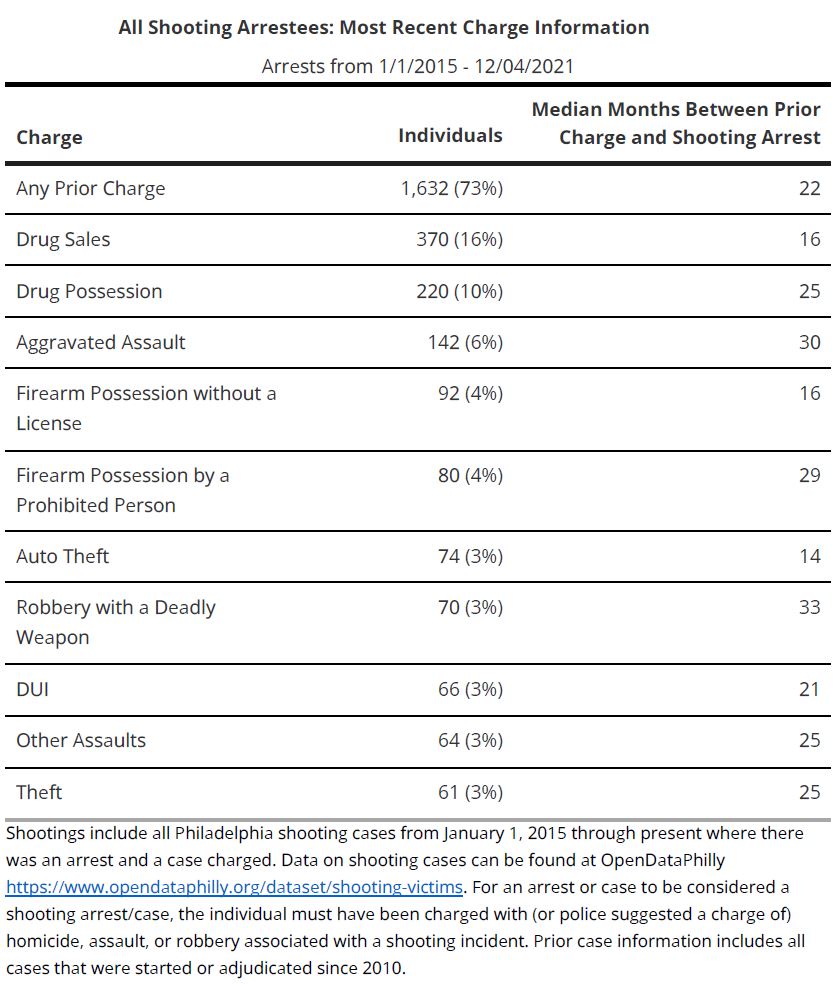

Throughout this collaboration the PPD and DAO have jointly reviewed information about shootings and arrests to consider factors that impact clearance rates in Philadelphia. We began by systematically reviewing the criminal histories of 100 people most recently arrested for shootings in Philadelphia, as of September 2020. We later expanded our review to all shooting arrestees since 2015. We found the groups were comparable across basic demographic and criminal legal factors, so we focused much of our analysis on the larger group. As of December 4, 2021, 2,249 people had been arrested for shootings in Philadelphia since 2015: 93% were male, 70% were under the age of 30, 76% had prior arrests, 51% had 3 or more prior arrests, 52% had a prior felony charge, 40% had a prior felony conviction, and 20% had pending court cases at the time of arrest. The most frequent prior charges include drug sales and drug possession, assaults, theft, robbery, and firearm possession without a license (see Appendix 7: DAO 4). For context, the prior charge histories of the 2,249 people arrested for shootings in Philadelphia since 2015 reflect the most common offenses people are arrested for in Philadelphia more broadly, including those never arrested for a shooting.

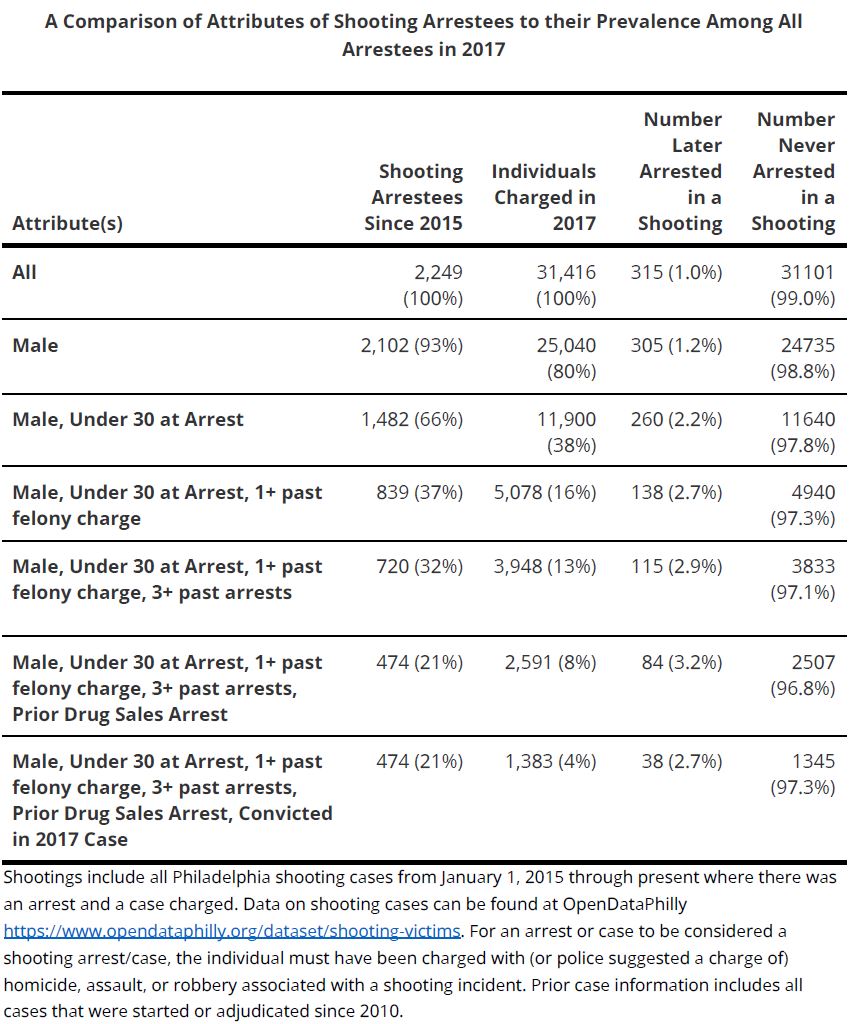

Although it may be appealing to consider building a predictive model to forecast future shooters and using it to incapacitate people who fit that model, the evidence does not support the idea that prior arrest patterns of people arrested for shootings in Philadelphia can be used to accurately forecast future shooters. There are several problems with such a model. First, due to very low arrest rates, any model would be based only on the small number of people who are actually arrested for shootings. This means that the model reflects on a small subset of people who may be completely different from the majority of shooting perpetrators. For example, it may be that law enforcement can more easily clear a case against a shooter who has a prior criminal record due to the availability of arrest photographs, contact information, and knowledge of specific prior crimes. If so, shooters who have no prior criminal record are likely under-represented among this group. Second, it would cast a very broad net: thousands of people arrested each year for a number of crimes match the most common characteristics of shooting arrestees (see Appendix 7: DAO 5). Although we could potentially prevent dozens of future shootings by jailing thousands of people, holding so many people who would never engage in a shooting to prevent the actions of a few raises grave moral and constitutional concerns. It would also require funding a massive increase in mass incarceration that would drain funding for prevention or smart enforcement (e.g., forensics) that is likely far more effective in reducing future gun violence than additional incarceration, but has never been attempted in Philadelphia. By contrast, such models could help identify a broad group of people who might benefit from additional support that would help prevent future system contact. Third, recent high-quality Gun Violence Task Force (GVTF) investigations have produced strong cases against individuals who had no prior record or had not been arrested for several years—highlighting the limitations of a predictive model based on who is arrested and reinforcing the importance of robust investigative work and investment in forensics to improve clearance rates and strengthen cases when there is an arrest.

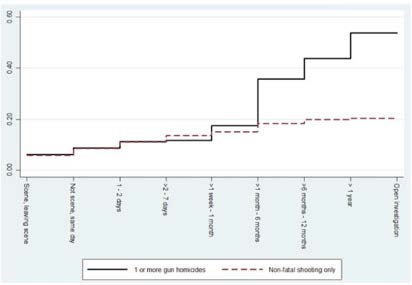

We also researched the social and system factors that impact shooting clearance rates. Using logistic regression, we considered how victim, incident, and police characteristics relate to clearance rates in fatal and non-fatal shootings. For non-fatal shootings, we found that investigations by units with more detectives were significantly more likely (α = 0.05) to be cleared than shootings investigated by units with fewer detectives; that shootings where the PPD Special Investigations Unit (SIU) responded were significantly more likely to be cleared than shootings where line detectives responded; and shootings with female victims were significantly more likely to be cleared than shootings with male victims. For fatal shootings, we found that shootings with white victims were significantly more likely to be cleared than shootings with Black or Latinx victims; that shootings with child victims (13 or younger) were significantly more likely to be cleared than shootings with older victims; and that shootings that occurred when it was light outside were significantly more likely to be cleared than shootings that occurred when it was dark outside (see Appendix 7: DAO 6).

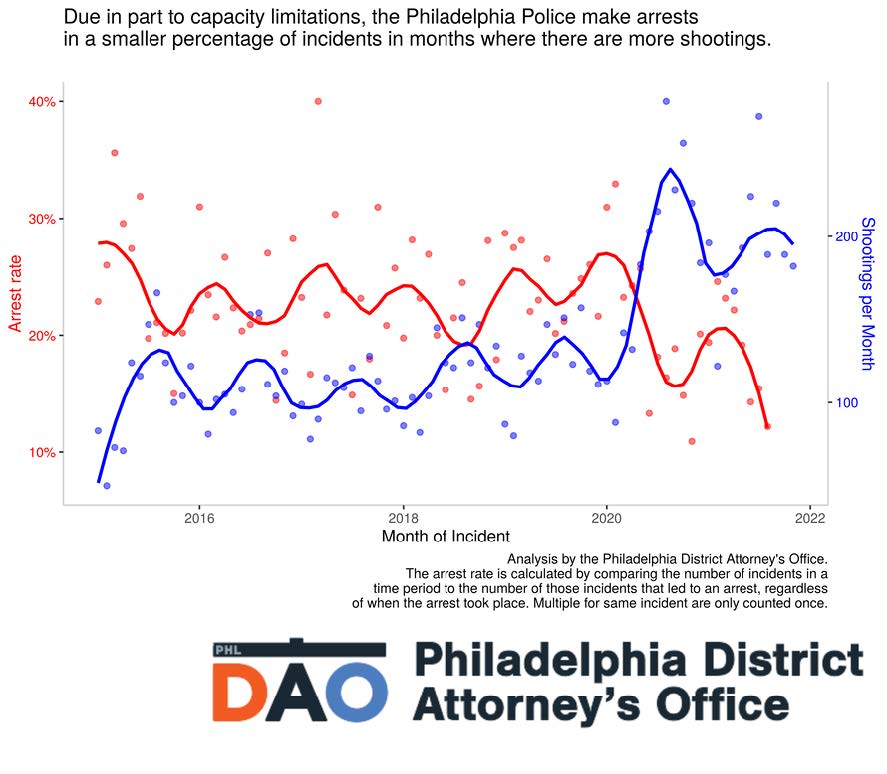

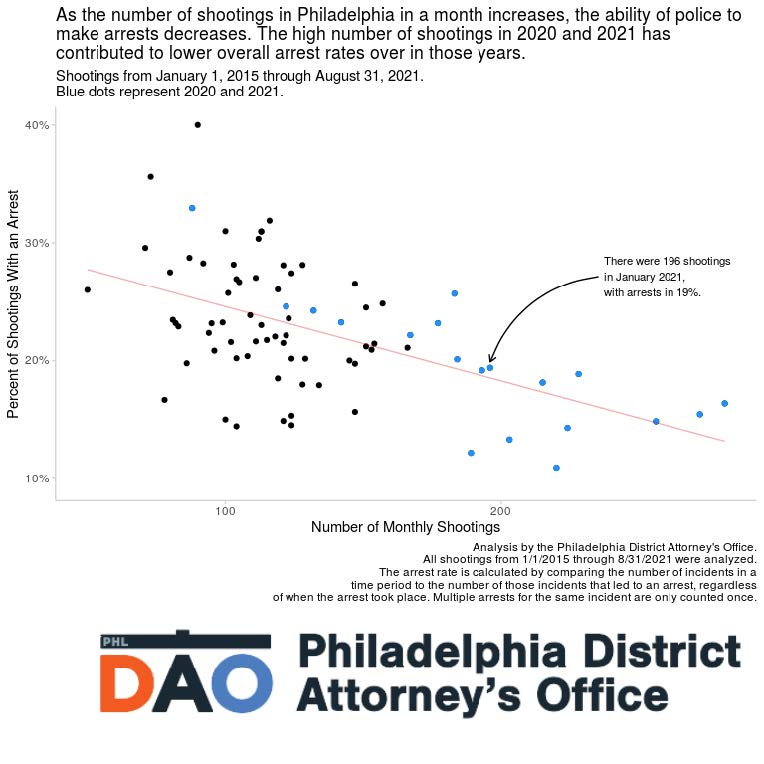

We also found that the number of non-fatal shootings that lead to arrest remained relatively flat regardless of the number of shootings in a month: in months with fewer shootings, the arrest rate was higher, and in months with high numbers of shootings, the arrest rate was lower (see Appendix 7: DAO 7). This suggests that capacity constraints in investigating non-fatal shootings hinder arrests: if there is a maximum number of shooting cases that can be investigated by the PPD at any point in time, as shootings rise, the arrest rate falls.

Finally, we used Philadelphia data to replicate an analysis done in Boston on how long it takes to solve shooting cases (Cook, Braga, Turchan, Barao, 2019).20 We found that the majority of arrests happen within the first few months following a shooting; for non-fatal shootings, 75% of arrests occur within 61 days, while for fatal shootings, 75% of arrests occur within 125 days (see Appendix 7: DAO 8). In Boston, researchers found that the difference in clearance rates between fatal and non-fatal shootings to be “primarily a result of sustained investigative effort in homicide cases made after the first 2 days” (Cook, Braga, Turchan, Barao, 2019).

Together, these findings suggest organizational changes within the PPD could improve clearance rates. By increasing the number of specialized investigators available to handle non-fatal shooting cases and equipping them with greater crime scene and modern forensic capacity, the police will be able to solve more shootings (see Recommendations).

Improving gun case outcomes

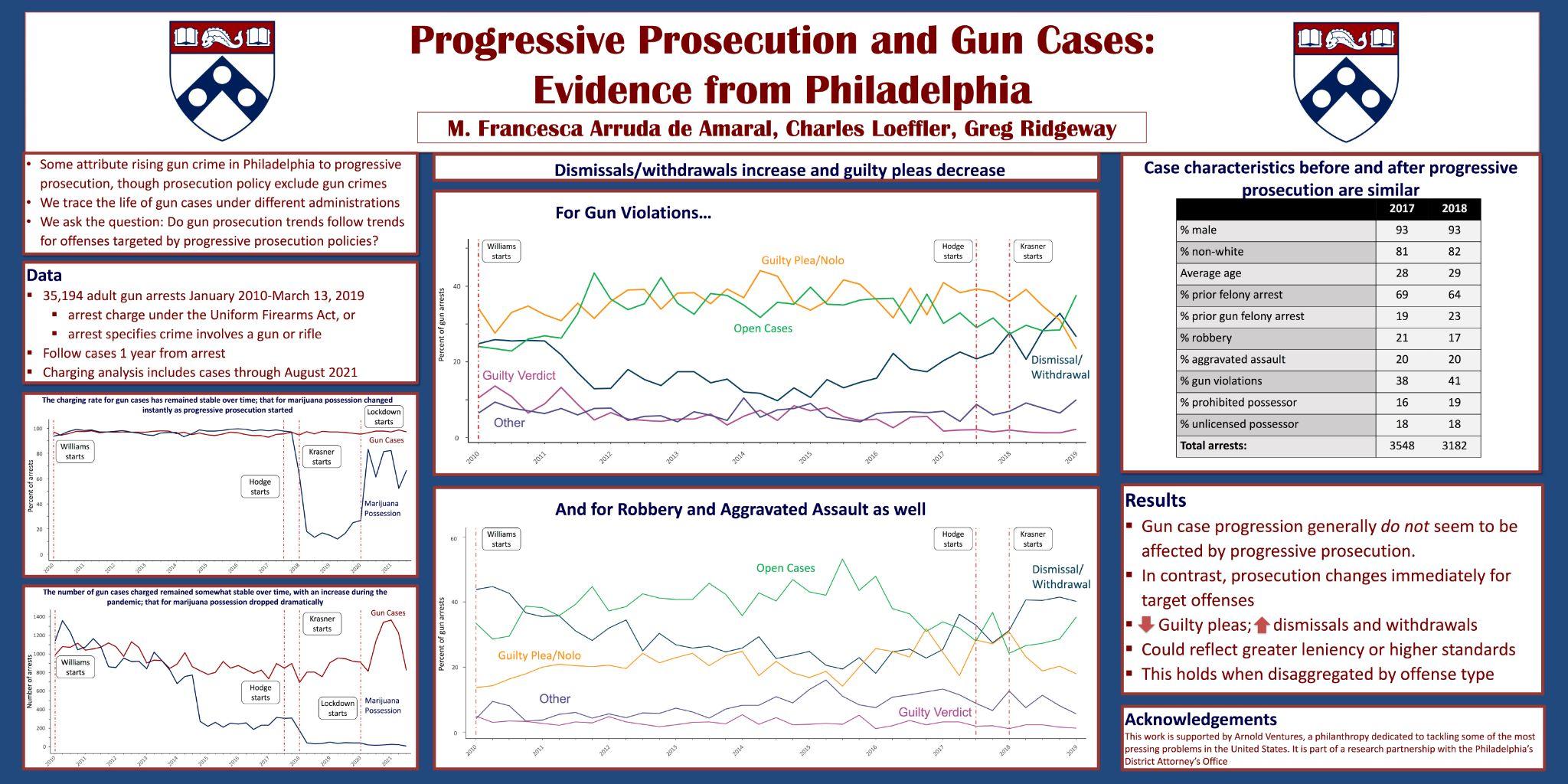

After an arrest is made, DAO prosecutors fully vet incident information about defendants, victims, witnesses, and evidence from police, and seek a conviction where the evidence is sufficient to show beyond a reasonable doubt that the individual arrested perpetrated a specific shooting. Although the DAO has consistently charged nearly every individual arrested by the police for a shooting,21 in recent years, the withdrawal and dismissal rates in a broad range of gun cases has increased while the conviction rate has decreased (Amaral, Loeffler, Ridgeway, 2021; see Appendix 7: DAO 9).22 In response, the DAO undertook a number of efforts to improve outcomes in gun and shooting cases, including combining the Homicide and Non-Fatal Shootings Units23 and working with the courts to prioritize prosecutions for non-fatal shootings.24 By the first quarter of 2020, which was immediately before the COVID pandemic effectively shut down the Philadelphia courts, the DAO’s conviction rate improved to 87% for fatal shooting cases and 78% for non-fatal shooting cases.

Following a DAO preliminary data analysis document the increase in withdrawals and dismissals in cases involving gun possession (but excluding shooting cases), the DAO undertook an intensive case file review of 400 randomly selected dismissed and withdrawn gun possession cases in summer 2020 to identify common reasons for those outcomes, and to find ways to improve gun possession cases. One of our main findings was an increase in “constructive possession” cases among dismissed and withdrawn cases. These are cases in which a recovered firearm was not actually physically possessed by the defendant at time of arrest (see Appendix 7: DAO 10). A constructive possession case might involve a gun found in the trunk of a car occupied by multiple passengers or a gun found under a car seat within reach of multiple passengers, none of whom own the car. It is the prosecutor’s burden to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that anyone charged both knew where the gun was and intended to exercise control over it. Merely proximity to a gun or knowing of its existence is legally insufficient to obtain a conviction. Constructive possession cases are far more challenging to prosecute than cases where a firearm is recovered from someone’s body.

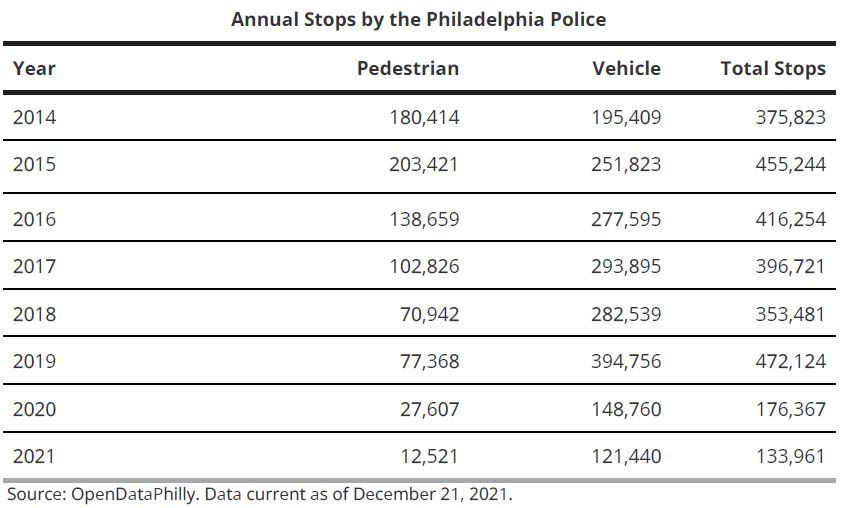

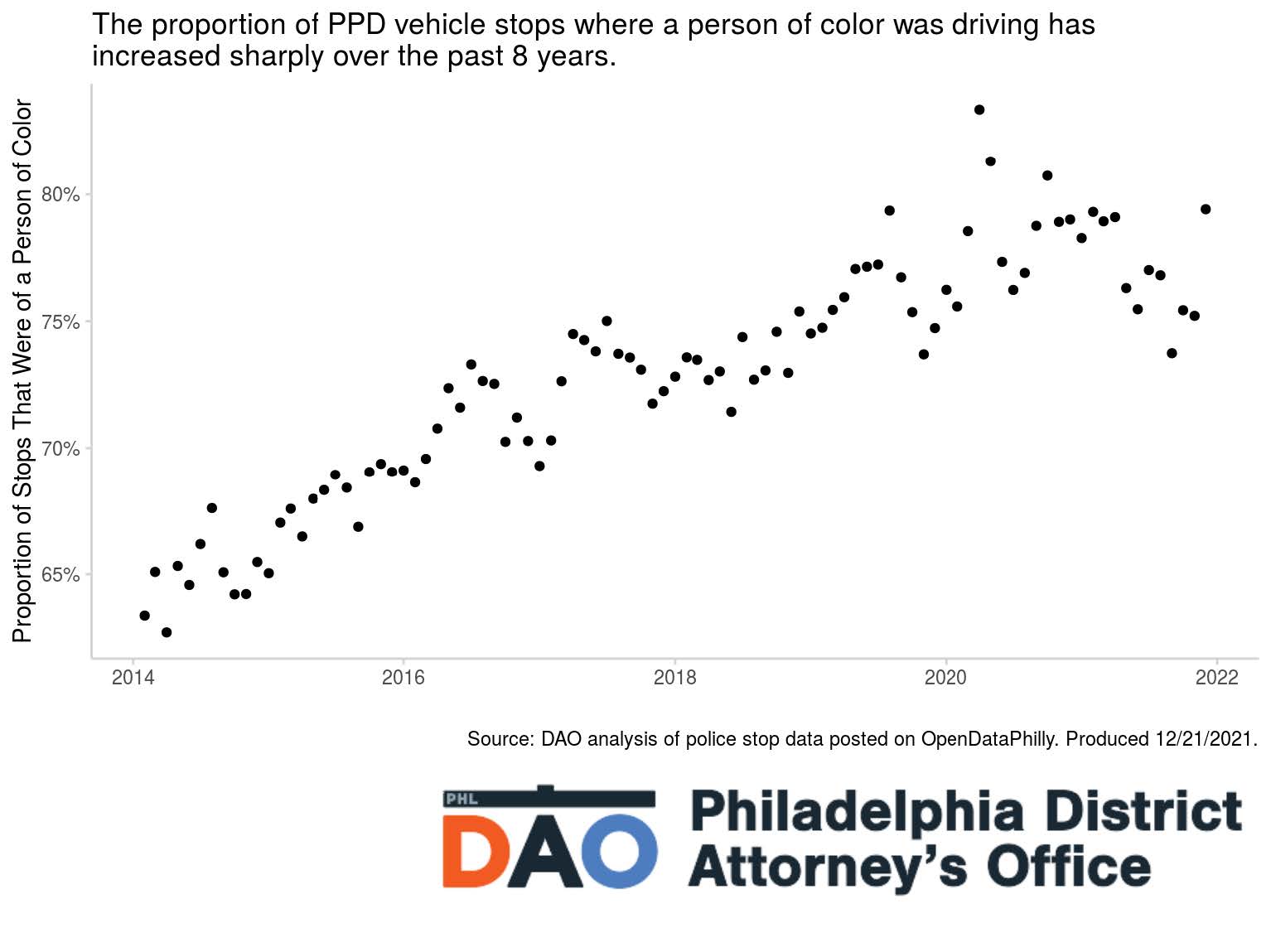

Such evidentiary issues present challenges in the legal system, and cases often stem from car stops—where legal standards for searches of private property apply. If police illegally search a person or place for a gun, the gun recovered will be excluded at trial, rendering a conviction for the gun impossible in nearly every case. It is much easier to prove who possessed a gun when that gun is found on someone’s person during a pedestrian stop, as compared to a gun recovered from the trunk of a car stopped with multiple occupants. The increase in car stops, where the person connected to the recovered gun is less clear, can be seen in data released as part of the city’s “stop and frisk” litigation (Bailey, et al. v. City of Philadelphia, et al., 2011).25 That data shows that while the number of pedestrian stops conducted by police has steadily decreased from 175,000 in 2014 to 75,000 in 2019 (i.e.,pre-COVID), the number of vehicle stops has sharply increased, from 193,000 in 2014 to 389,000 in 2019. Overall, since 2014, Philadelphia Police have conducted 791,000 pedestrian stops and 1,929,000 vehicle stops (see Appendix 7: DAO 11).

Three recent court rulings have also changed both the policing and prosecution of gun possession cases, making them more challenging: Commonwealth v. Hicks (2019)26 found that the police were not allowed to stop individuals merely because they possessed a concealed firearm and showed it to another person while police watched; Commonwealth v. Perfetto (2019)27 required that traffic cases and criminal cases stemming from those traffic cases must be tried together or risk the criminal case being dismissed; and Alexander v. Commonwealth (2020)28 required that the police seek a warrant to search a car during a car stop, rather than be allowed to search with mere suspicion of contraband. All three of these opinions apply retroactively and impact the growing backlog of active cases, and have resulted in a higher proportion of cases that have not resolved with a conviction. Responsive changes in police and prosecutor practice are needed and are being implemented in order to ensure cases are opened with evidence that will be admissible at trial.

In addition, unavoidable court closures due to COVID have very significantly hampered our ability to prosecute cases in a timely fashion. As a result, few cases have been resolved overall, and only cases that could be resolved quickly and without need for witnesses were resolved—leading to an unusually high number of dismissals as compared to convictions. To illustrate this, at the end of 2019, there were 182 pending fatal shooting cases and 261 non-fatal shooting cases open in the courts. As of mid-December 2021, there were 460 fatal shooting and 650 non-fatal shooting cases open. Firearm possession by a prohibited person increased from 615 to 1,177 over the same time period, while firearm possession without a license cases more than tripled, from 628 to 2,284 (see Appendix 7: DAO 12). With these limitations, less serious firearm possession cases are disposed of more quickly and efficiently, while more serious cases awaiting trial or plea negotiation with defense counsel take longer to complete. As courts resume, the percentage of cases resolved with a conviction should return to pre-COVID levels as the case backlog is addressed. Perhaps most importantly, the unavoidable reduction in available trial rooms for jury trials and bench trials have disincentivized defendants, especially those who are out of custody or face potentially lengthy sentences, to resolve their cases in the near future.

In Summer 2020 the DAO established a DAO Intelligence Unit to improve the collection and dissemination of information with DAO Investigative and Trial Units, the PPD, and other local, state, and federal law enforcement partners. The Intelligence Unit expanded in January 2021, and now has an Intelligence Analyst stationed at the Delaware Valley Information Center (DVIC), helping the Intelligence Unit function as a centralized point-of-contact for receiving intelligence from the PPD, improving collaboration and communication. The Intelligence Unit maintains, organizes, and disseminates intelligence information collected by the DAO and law enforcement partners to ADAs, and also works closely with the PPD to identify drivers of violence crime and to prioritize these drivers of violence crime for arrest, charging, and prosecution.

To strengthen cases in light of the increase in firearms recovered from vehicle stops and higher legal standards to search, in December 2020 the DAO and PPD began meeting weekly to review VUFA (or gun possession) and non-fatal shooting arrests made the previous week. Led by the Deputy Commissioner of Investigations in the PPD and the Director of Intelligence in the DAO, this collaboration includes PPD Detectives, Assistant District Attorneys (ADAs) who have reviewed the cases, ADAs from the Law Division who provide guidance on changing legal standards, and data personnel to track progress. The weekly VUFA and non-fatal shooting case review proactively focuses on improving cases at an early stage by creating a dialogue among members of the DAO and PPD, helping to identify evidentiary issues sooner to bring the strongest cases possible. Individual cases as well as case trends are improved through systematizing discussions of evidentiary needs and by offering guidance on the implications of changes in the law for police practice, training, and policy. Over 2,300 cases were reviewed between December 2020 and 2021, and the proportion of cases that passed the preliminary hearing improved following the implementation of the collaborative review process: of the 1615 cases that received a preliminary hearing, 81% were successfully held for trial and are awaiting final disposition (see Appendix 7: DAO 13). We reduce harm to the community and enhance system efficiency by identifying and correcting evidentiary issues early and strengthening the cases we do bring so they are more likely to result in conviction.

Just as the weekly VUFA/non-fatal shooting review shows that outcomes are improved through collaboration, the Gun Violence Task Force (GVTF) in the Philadelphia DAO shows the importance of conducting high-quality, often longer-term and collaborative investigations that generate strong cases. One strategy the GVTF uses is to identify group conflicts, and then find cold cases associated with those conflicts. Utilizing social media, electronic forensic evidence, and the Grand Jury process to facilitate witness participation, the GVTF engages in targeted prosecution of people who are driving gun violence, often seeking high bail or no bail eligibility following an arrest. See, for example, recent investigations that produced strong cases, including against individuals who had no prior record or had not been arrested for several years (see Appendix 7: DAO 14).

Taken together, a range of factors have produced a long-term trend where more gun cases, particularly those involving charges of gun possession, are being withdrawn or dismissed. We have been working to address this by implementing institutional changes in the DAO and developing collaborative processes and practices with our partners, especially the PPD. These include combining the DAO’s Homicide Unit with Non-Fatal Shootings, creating the DAO Intelligence Unit, expanding the GVTF in the DAO, and developing the non-fatal shooting track in partnership with the courts and the VUFA/NFS review process with the PPD, among other initiatives.

Deterrence of illegal firearm possession

One frequently cited way to reduce shootings is to enhance enforcement against illegal possession of firearms29—in spite of little research supporting the approach (Peterson and Bushway, 2020).30 Because of the ease in accessing guns and the relative threat that some feel if they do not carry a gun, we do not believe that arresting people and convicting them for illegal gun possession is a viable strategy to reduce shootings. Some people who illegally possess firearms in Philadelphia present a real danger to the community and merit vigorous prosecution to conviction and incarceration. Others are basically law-abiding people who have not obtained a license. There is a huge difference between these two groups and public safety requires that they be held accountable in different ways. It is at best ineffective and at worst counterproductive for the police to treat these groups the same and focus on enforcement of firearm possession laws rather than focus on shootings. More resources are needed to deter shootings through police presence in communities, through a higher capacity in forensics, and more detectives to investigate and solve shootings when they occur. Our analysis of the data also finds that—contrary to recent statements from some city officials and in spite of the obvious point that guns are used in shootings—very few people arrested for illegal gun possession are later arrested for committing a shooting (see Appendix 7: DAO 15).

To deter someone from an act through enforcement, one has to ensure that the punishment for that act is 1) certain and 2) swift. Our experience in Pennsylvania and the U.S.—a state that has outpaced national incarceration rates and has among the most severe sentences in a country with the highest incarceration rate and longest sentences in the world—is that severe punishment has not been successful in deterring people from carrying guns or shooting people. With respect to gun possession, deterrence requires that the state sanctions for illegal gun possession are more certain and swift than the risk of not carrying a gun.31 In Philadelphia, this presents a challenge: we are a City and Commonwealth awash in guns32 and with a high number of shootings and low clearance rates, people do not feel protected by the police or other government agencies or local resources. These two factors create a situation where some people view the risk of being caught by police with an illegal gun as outweighed by the risk of being caught on the street without one (Sierra-Arévalo, 2016; Fontaine, La Vigne, Leitson, Erondu, Okeke, Dwivedi, 2018).33

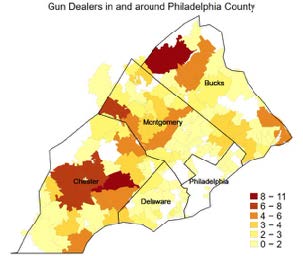

The number of guns in the U.S., Pennsylvania, and Philadelphia is overwhelming, in great part because of weak state and federal regulations that make it impossible to know exactly how many guns are in a community and who is in possession of them. There were more than 12.9 million guns legally sold or transferred in Pennsylvania between 1999 and 2020, an average of over 1,600 per day; 266,186 were sold in Philadelphia (33 per day), and 1,824,614 in Philadelphia, Bucks, Montgomery, Chester, and Delaware counties combined (227 per day) (Pennsylvania State Police, n.d.).34 From 1999 through 2019, only 165,717 guns were seized by law enforcement in Pennsylvania, fewer than 22 per day, with the PPD accounting for more than half (97,905, or 12 per day) (Attorney General’s Office, n.d.).35 That means that, each day in Philadelphia over the last 20 years, for every 3 guns legally bought or sold (i.e., in circulation that we know about), roughly 1 “crime gun” was seized (i.e., removed from circulation). Compounding the problem, in Philadelphia, only 1 in 4 recovered “crime guns” were purchased in Philadelphia (Attorney General’s Office, n.d.), and only half of crime guns seized by law enforcement statewide were purchased in Pennsylvania; the rest were purchased out of state or have no known origin (see Appendix 7: DAO 16).

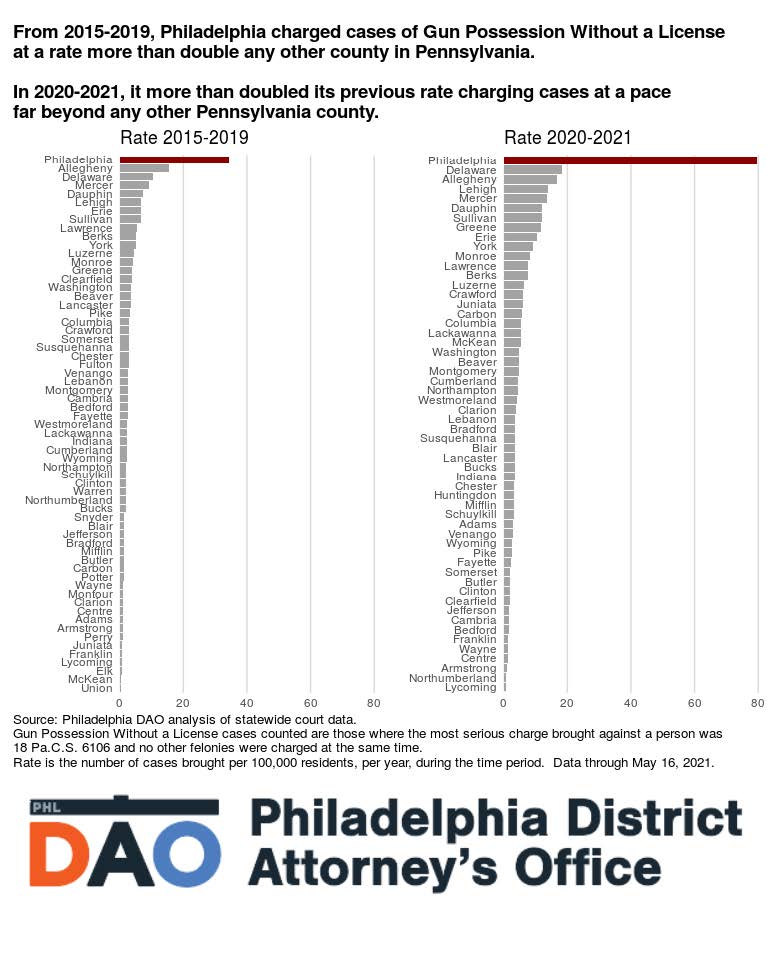

With so many guns available, a law enforcement strategy prioritizing seizing guns locally does little to reduce the supply of guns, and, if it entails increasing numbers of car and pedestrian stops, has the potential to be counterproductive by alienating the very communities that it is designed to help. People of color are disproportionately stopped in Philadelphia and arrested for illegal gun possession in Philadelphia and statewide. As the use of vehicle stops has increased, the proportion of PPD vehicle stops where a person of color was driving increased sharply during the same time period, regularly approaching 80% in recent years (see Appendix 7: DAO 11). In Philadelphia, approximately 80% of people arrested for illegal gun possession are Black; statewide, approximately 66% are Black (see Appendix 7: DAO 17). Focusing so many resources on removing guns from the street while a constant supply of new guns is available is unlikely to stop gun violence, but it does erode trust and the perceived legitimacy of the system. This in turn decreases the likelihood that people will cooperate and participate in the criminal legal system and associated processes, reducing clearance, conviction, and witness appearance rates.

It is again worth noting the inequity perpetuated by our state legislature, which made it a felony to carry a firearm without a license in only one county, Philadelphia, which is also its most diverse county. All state prisons in Pennsylvania are located in counties other than Philadelphia.36 And many of those counties have lost their steel and coal industries, only to replace them with a state prison industry that brings tremendous financial and political benefit to those counties (Remster and Kramer, 2019). Those financial and political benefits only flow fully if those state prisons cells are occupied. It does not appear that our state legislature’s primary interest is incarcerating people who carry firearms without a license. Our legislature’s primary interest is incarcerating Philadelphians, most of them Black and brown, in their far less diverse counties for the money and the power it brings them. Philadelphia should recognize this commerce in Philadelphians’ bodies for what it is—referred to in scholarship as “prison gerrymandering” (see Remster and Kramer, 2019 for a study of prison gerrymandering in Pennsylvania).

Improving victim and witness appearance rates

Prosecution in the criminal legal system relies on the participation of civilian witnesses and other actors, such as arresting officers, to present and authenticate evidence necessary to prove every element of a crime beyond a reasonable doubt. A DAO analysis found that victim and witness Failure to Appear (FTA) in court is the cause of approximately half of all gun possession cases being dismissed or withdrawn in Municipal Court (see Appendix 7: DAO 18). This is an obvious problem that needs to be remedied.

While there is often attention placed on defendants failing to appear, a preliminary analysis of misdemeanor cases in Philadelphia found that it is more likely that at least one non-defendant will fail to appear for at least one hearing (e.g., victim, witness, law enforcement officer, or attorney) than it is for a defendant to fail to appear (Graef and Ouss, 2021). When witnesses or court actors (e.g., law enforcement, attorneys) do not appear, at best cases require multiple listings to resolve, and in some instances cases may be dismissed due to a lack of key testimonial evidence.

In a study of Philadelphia misdemeanor cases, witnesses and victims were most likely to miss at least one hearing in cases involving violent crime. Police, by contrast, were likelier to miss appearing to testify in less serious incidents (e.g., traffic, drug, public order, property); defense attorneys also sometimes did not appear in these less serious cases. Reasons given for law enforcement failing to appear included being sick (30%), injured on duty (IOD) (12%), on vacation/out of town (10%), or no reason given (26%) (Graef and Ouss, 2021, see Appendix 7: DAO 18).

The DAO has received grant funding and continues to seek additional funding to develop the technological capabilities necessary to maintain communications with victims and manage the Victim Witness Services (VWS) Unit caseload.

- The $4.6M grant the DAO received to create the District Attorney’s Transparency Analytics (DATA) Lab also supported the hiring of developers for the DAO’s Information Technology (IT) Unit to create a custom-built case management system, “DA-Work Station” (DAWS). This will help us to better manage our cases, including allowing VWS to better track their contacts with victims and witnesses.

- The DAO has applied for grant funding to offer text messaging services that the DAO IT Unit would integrate with DAWS. Well-crafted text message reminders help increase witness appearance rates in court (Cooke et al, 2018).37

New technologies will be critical going forward, including DAWS and solutions like text messaging that help DAO Victim Witness Coordinators communicate with victims and witnesses. These technologies and tools will be especially needed as arrest clearance rates improve, allowing the DAO VWS Unit to provide support to more victims and witnesses (state funding only allows the DAO VWS to work with victims after an arrest is made).

Beyond improving technological systems, the analysis by Graef and Ouss (2021) also suggests that systemic change could improve witness appearance rates: reducing the volume of non-violent misdemeanor arrests would reduce the number of cases where police are required to but often do not appear. This would improve both system efficiency, and perhaps the experiences of victims and witnesses in misdemeanor cases. When a court case fails to advance because of a court actor’s FTA, causing further hardship in terms of travel, missed work or school, or with childcare or other logistical issues among those who do appear to testify, public confidence and trust in the system erodes. Improving officer appearance rates in misdemeanor cases is not a viable strategy, as that would remove officers from the streets of the communities where they are needed to deter gun violence with their physical presence. Furthermore, for many cases misdemeanor enforcement has been shown to be criminogenic (Agan, Doleac, Harvey, 2021). Notable progress has been made in Philadelphia since 2015 and during COVID to reduce arrests for property and drug offenses; there were over 20,000 property and drug arrests in 2017, and fewer than 10,000 property and drug arrests in 2021 (Palmer & Orso, 2021).38 Therefore, criminal justice partners must continue to collaborate to reduce prioritizations of arrests and prosecutions for low-level offenses, particularly against people who are in crisis due to poverty, homelessness, mental illness, or substance use disorder (Shefner, Sloan, Sandler, & Anderson, 2018).39

- Goals and Policy Considerations

In order to guide the analysis and to support the development of policy recommendations, the Committee has set the below policy-oriented goals that go beyond the original resolution’s descriptive goal of analyzing 100 shooter characteristics.

- Reducing gun violence through Deterrence of illegal firearm possession; Improving gun case outcomes; Improving shooting incident clearance rates; Improving witness appearance rates.

Additionally, given the importance of the long-term, sustainable solution to prevent gun violence, the data-sub committee took the liberty of adding the below two goals:

- Reducing gun violence through short term investments in community driven solutions for prevention

- Reducing gun violence through upstream, long-term investments in communities most impacted by gun violence for sustainable reduction

The next section, 6. Recommendation, discusses specific, actionable programs and practices to accomplish these goals.

- Recommendations by the DAO

Recommendations by the DAO

Improving shooting clearance rates

Support the PPD’s Creation of a Non-Fatal Shooting Investigation Unit

As our analysis shows, the PPD is most effective at solving shootings when the investigation is undertaken by a unit trained in and dedicated to solving shootings. (see Appendix 7: DAO 6, DAO 8). We support the PPD’s research-informed decision to create a dedicated Non-Fatal Shooting Investigation Unit (Cook, Braga, Turchan, Barao, 2019).

Invest in Forensic Technology

One of the clear lessons of the DAO’s Conviction Integrity Unit work—which has, to date, exonerated over 20 people nearly all of whom were innocent and spent decades in jail)103—is that Philadelphia has long lagged peer cities in investing in forensic DNA technologies to improve fatal and non-fatal shooting clearance rates and gun case outcomes. This technical forensic obsolescence leads to weak investigations, cases that fail in court for want of strong evidence, and, at worst, wrongful convictions of innocent people. This is no reflection upon Police Commissioner Outlaw or the excellent director of the PPD’s Office of Forensic Science (OFS), Dr. Michael Garvey, both of whom inherited a PPD culture in Philadelphia that they did not make.

Enhancing the capabilities and capacity of the OFS to test certain kinds of ballistic evidence taken from all or nearly all gun violence crime scenes for DNA could massively increase clearance rates for these crimes, and the addition of robust DNA evidence would strengthen cases, improving just outcomes and helping prevent wrongful convictions. In addition to improving cases going forward, forensic technologies could help bring accountability and closure in some of the nearly 9,000 shootings since 2015 for which there have been no arrests by identifying incidents with the same DNA to provide new leads and spur additional investigations. Serious investment in forensic cell phone analysis technology is also necessary, as cell phones provide many kinds of compelling evidence to solve and prosecute gun violence. The DAO’s Gun Violence Task Force has invested in a small amount of cell phone forensic technology that, in collaboration with PPD, has proven very successful as an investigative tool. That success should be expanded.

Ideally, a great city like Philadelphia would not only have a great director of the PPD’s OFS and a Police Commissioner increasingly supportive of forensics as an investigative tool (as Philadelphia does now), but it would have the space, staffing and funding necessary to make a huge difference in gun violence. OFS space would triple to about 150,000 square feet. Staffing would increase significantly after a period of hiring and training. Capacity to process evidence would massively increase with an increase in staffing for PPD crime scene personnel. The one-time price tag for this massive improvement would be approximately 5% of the PPD’s annual budget, which is quickly approaching $1 Billion. Serious improvement in forensics could be made for less than 5% in one-time expense. Either way, some annual expenses would also increase. However, every dollar invested would come back to the city, with dividends, in avoiding future litigation brought by innocent and wrongfully convicted people, in saving the cost of incarcerating the innocent, and in all the economic improvements and tax base improvements that accompany effective reduction of violent crime.

Improving gun case outcomes

Institutionalize Interagency Collaborations and Processes

Changes in gun case outcomes are part of a long-term trend reflecting shifts in the law and law enforcement practices, among other factors. We have been working to address this trend by implementing institutional changes in the DAO and developing collaborative processes and practices with our partners. These include combining the Homicide and Non-Fatal Shooting Units, creating the Intelligence Unit, and expanding the work of the GVTF in the DAO (including to handle preliminary hearings in gun cases), and developing the non-fatal shooting track in partnership with the courts and the VUFA/NFS review process with the PPD. The DAO recommends continuing to support these new initiatives, and looks forward to incorporating the PPD’s new Non-Fatal Investigations Unit into these collaborations and processes.

Invest in and Expand DAO Collaborative Intelligence, Investigations, Community-Centered, and Victim-Centered Efforts

Invest in the DAO’s recent expansion of its collaborative intelligence, investigative, community-centered, and victim-centered efforts, all of which are aimed at effective prosecution of gun violence, intervention in communities that suffer from gun violence, and prevention in underserved and traumatized communities. These investments would support competitive salaries, new positions (e.g., analysts in the Delaware Valley Information Center (DVIC), social media analysts, personnel to support 57 Blocks Initiative), and new initiatives (e.g., Intelligence Unit; Gun Crime Strategies; expanding Crisis Assistance, Response, and Engagement for Survivors (CARES); diversion expansion; 57 Blocks Initiative), including new efforts undertaken in the last few years without additional funding that were supported by both the PPD and DAO.

Improving victim and witness appearance rates

Prioritize Building Trust Between Communities and Law Enforcement

Building trust should improve clearance rates, witness appearance rates, and gun case outcomes, and therefore should be a top priority of all agencies. Trust can be developed in many ways, including by increasing positive interactions with law enforcement and elevating community engagement. Research in New Haven, Conn., found that “a single non-enforcement interaction can, in fact, improve the public’s attitudes toward police” (Sierra-Arévalo, 2019). In the study, half the residents who received a baseline survey were then randomly selected to receive a “non-enforcement interaction with a uniformed officer in which the officer introduced themselves, asked about neighborhood issues, and then gave the resident a business card with the officer’s hand-written work phone number” (Sierra-Arévalo, 2019). Results found “that one non-enforcement community policing interaction markedly increased residents’ perceptions of police legitimacy and willingness to cooperate with police [… and] the results were strongest among Black residents and those with more negative attitudes about police” (Sierra-Arévalo, 2019).

Reduce Counterproductive Misdemeanor Arrests and Cases

Meanwhile, police should engage in less misdemeanor enforcement to build trust, improve appearance rates, and so that they can spend a higher proportion of their time deterring or working on more serious cases. This would require additional support for non-law enforcement responses to many events police are currently called to respond to (Ratcliffe, 2021)104, but would also reduce the burden to other system actors from prosecuting and processing these cases in the court system. According to August Vollmer, the “Father of American Policing,” the enforcement for crimes of morality, such as substance use and sex work, should “not [be] a police problem; [drug addiction] never has been and never can be solved by policemen” (Vollmer, 1936, 117-8)105. Involvement in such enforcement “engenders disrespect both for law and for the agents of law enforcement” (Vollmer, 1936, 237). Problems with misdemeanor enforcement—which research has found to be criminogenic (Agan, Doleac, Harvey, 2021)106—are exacerbated when witnesses, including law enforcement, do not appear in court to testify in those misdemeanor cases. When a court case fails to advance because of a court actor’s FTA, causing further hardship in terms of travel, missed work or school, or with childcare or other logistical issues among those who do appear to testify, public confidence and trust in the system erodes. Improving officer appearance rates in misdemeanor cases is not a viable strategy, as that would remove officers from the streets of the communities where they are needed to deter gun violence with their physical presence, e.g., on foot patrols. More low-level offenses and misdemeanors could be handled with citations, like the city did with cannabis (PPD Directive 3.23, 2021).107 Therefore, criminal justice partners must continue to collaborate to reduce arrests and prosecutions for low-level offenses, particularly of people who are in crisis due to poverty, homelessness, mental illness, or substance use disorder.

Invest in Communication Technology, Transportation, Relocation, and Trauma Support for Victims and Witnesses

The DAO has been investing and continues to seek funding to improve its technological infrastructure, which has not kept pace with advancements and changes in how people communicate, among other issues. Correspondence sent through the mail is slow and ineffective, and busy schedules can make it hard to find time to connect on the phone, so communicating via text messages and cell phone applications offers a promising way to improve victim and witness experiences with the criminal legal system and appearance rates. To begin to improve its technological infrastructure, the DAO received funding to build a new custom case management system in-house, including a new module for the Victim Witness Services (VWS) Unit. In addition, the DAO is seeking external partnerships and funding to utilize text messaging tools to quicken and improve our ability to communicate with victims and witnesses via text messages and phone apps.

- Text messaging services are used by the Defender Association of Philadelphia, and in hundreds of jurisdictions across the U.S.

- In addition to facilitating communication, text messaging can be used to coordinate services for victims and witnesses with community-based organizations, make it easier for victims to file paperwork to receive compensation and send Victim Impact Statements, and provide transportation vouchers (see below)

- Since 2010, there have been over 2,500 cases where either intimidation or retaliation were charged in Philadelphia, and there would likely be more but for the lack of additional technologically-mediated reporting mechanisms.

Therefore, the DAO recommends increasing local investment in technology to facilitate communication with victims and witnesses.

Due to funding limitations, the DAO is only able to offer free transportation to court in the form of van rides or ride-share vouchers to people who are elderly and/or disabled. Among low-income clients, reasons frequently cited for not appearing in court include a lack of transportation or a lack of childcare. Expanding our free court transportation program would allow us to also send ride vouchers to those who simply lack transportation or live in areas of the city where public transit is not as easily accessible. We also supply a discounted parking voucher to aid victims willing to drive to court. However, the discount is so small that many victims on low or fixed incomes are still unable to afford the parking cost. This is also a problem for victims dealing with mobility issues, as the only parking garage that supplies vouchers is several blocks away from both courthouses. Transportation logistics could be organized through a mobile app, which would allow people to sign up for transportation vouchers and let the DAO send ride-share vouchers through messaging on the app. Therefore, the DAO recommends vastly increasing its capacity beyond only providing transportation to those who are elderly and/or disabled to instead provide free rides to court for every victim or witness who has a need.

Beyond staying in touch and helping with transportation to court, sometimes people need to relocate from their home and community to feel safe participating in the criminal legal process. The Witness Relocation Program is intended to quickly assist in the relocation of witnesses from areas where they are victims of real or potential intimidation, harassment, or harm because of their witness status. Assistance may include, but is not limited to, reasonable moving expenses, security deposits, rental expenses, storage unit rental, P.O. Box fees, and utility startup costs. The aim is to help victims and witnesses relocate without financial loss or reduction in their standard of living. This assistance includes facilitating moves within Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA), which can take time; the DAO advocates on behalf of victims/witnesses to substantially reduce the PHA waitlist timeline and to assist with relocation costs.

Relocation may include multiple family members. Currently, victim service staff regularly shift families from one impoverished neighborhood to another with similar crime rates, neighborhoods that may only be blocks away from the location where the underlying crime occurred. The need to relocate families is extremely high and, as a result of the crime oftentimes occurring within feet of the family residence or victim’s home, there is an enormous amount of trauma and fear for family members (especially children). Most families are unable to move from the area of danger due to financial barriers. Furthermore, some victims/witnesses may not qualify for certain relocation assistance programs (such as the PAAG’s Witness Relocation Program) due to criminal history, lack of cooperation with law enforcement, or other factors.

Depending on the family size, financial barriers to relocation, and the need to utilize temporary lodging accommodations, relocation expenses can be substantial; current funding levels do not meet the level of need, which is certainly substantial, with over 550 homicides and numerous shootings. Given that the DAO has seen an increase in the amount relocation referrals not qualified for State assistance (50% of relocation referrals received in 2021 do not qualify for the PAAG program, compared to only 15% in 2018), it will be necessary to increase our office’s relocation budget in order to assist community members who may not meet State requirements. Currently, the budget for 2022 is $260,000, though the allocation tends to vary year-to-year; e.g., it was $165,000 in 2018. The DAO recommends increasing the budget of the Witness Relocation Program to at least $1 million dollars to improve the ability of the legal system to achieve justice by relocating more people so they can feel safe and participate as witnesses. Combined with strong safety planning, hard work by victim advocates on a case-by-case basis, and other relocation dollars, more resources would create a greater impact for those in most need of this type of support, and improve witness appearance rates. This is, in effect, an effort to be more inclusive when it comes to assisting community members who are directly and indirectly affected by violent crime.

Preventing gun violence in the community

Invest in Community- and Place-Based Non-Law Enforcement Solutions in Historically Traumatized and Under-Resourced Communities at Risk of Gun Violence

Structural racism has caused disinvestment and poverty in specific areas of Philadelphia, which has, in turn, created the conditions in which shootings occur (see Appendix 7: DAO 1). Law enforcement cannot solve systemic divestment. Philadelphia needs to proactively work to end the de facto redlining of poor Black communities, expand new investment and living-wage jobs in Black communities through monies from the American Relief Act and the recent Infrastructure legislation, use new techniques like the proposed Philadelphia public bank to invest in Black communities, and sanction or prosecute institutions that discriminate. We must see the availability of affordable housing throughout Philadelphia and the fair and full funding of our schools as central to our crime prevention strategy.

The DAO recommends making coordinated and targeted investments of money and resources in parts of Philadelphia harmed by structural racism, including financial investments in community-based violence prevention efforts and city services that do not involve law enforcement. Some of the most rigorous evidence we have that non-law enforcement strategies can reduce violence is based on research conducted in Philadelphia (South, 2021). There is evidence that the following strategies lead to reductions in violence in Philadelphia, while improving other positive outcomes:

- Greening vacant lots (Branas et al, 2018)108

- Planting trees (Branas et al, 2018)

- Picking up trash (Branas et al, 2018)

- Structurally repairing occupied homes (South, MacDonald, Reina, 2021)109

- Remediating abandoned houses (MacDonald, n.d.)110

In addition to the above Philadelphia-based research, there is evidence from Chicago that improving street lighting can reduce crime (Chalfin, Hansen, Lerner, Parker, 2021).111 Recent reporting on issues with repairing lighting in Philadelphia underscore the need to include such non-law enforcement responses in any broader violence prevention strategy (Marin and Briggs, 2021).112 In addition to prioritizing responding to 311 calls in areas most impacted by gun violence, the DAO recommends developing and implementing a place-based non-law enforcement violence-prevention plan that proactively targets areas most impacted by gun violence, redlining, and mass incarceration and supervision for positive improvements, such as greening vacant lots, planting trees, picking up trash, repairing occupied and abandoned homes, and improving lighting. The DAO is working to create such a plan: the “57 Blocks Initiative.”

Create Fund Modeled on The Chicago Fund for Safe and Peaceful Communities to Increase Private and Institutional Funding for Philadelphia-Based Community Gun Violence Prevention Organizations